People who do surveys using random-digit phone number dialing tend to think that random-digit dialling or similar attempts to sample in a representative way are very important, and sometimes attack the idea of public-opinion inference from convenience samples as wrong in principle. People who use careful adjustment and matching to calibrate a sample to the target population are annoyed by this, and point out that not only is statistical modelling a perfectly reasonable alternative, but that response rates are typically so low that attempts to do random sampling also rely heavily on explicit or implicit modelling of non-response to get useful results.

Andrew Gelman has a new post on this issue, and it’s an idea that I think should be taken more further (in a slightly different direction) than he seems to.

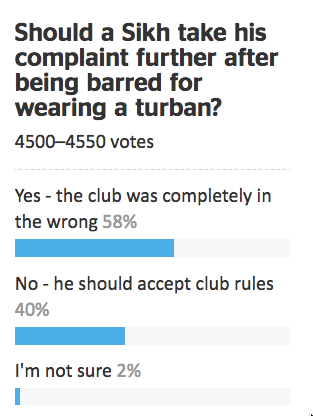

It goes like this. If it becomes widely accepted that properly adjusted opt-in samples can give reasonable results, then there’s a motivation for survey organizations to not even try to get representative samples, to simply go with the sloppiest, easiest, most convenient thing out there. Just put up a website and have people click. Or use Mechanical Turk. Or send a couple of interviewers with clipboards out to the nearest mall to interview passersby. Whatever. Once word gets out that it’s OK to adjust, there goes all restraint.

I think it’s more than that, and related to the idea of signalling in economics or evolutionary biology, the idea that peacock’s tails are adaptive not because they are useful but because they are expensive and useless.

Doing good survey research is hard for lots of reasons, only some involving statistics. If you are commissioning or consuming a survey you need to know whether it was done by someone who cared about the accuracy of the results, or someone who either didn’t care or had no clue. It’s hard to find that out, even if you, personally, understand the issues.

Back in the day, one way you could distinguish real surveys from bogus polls was that real surveys used random-digit dialling, and bogus polls didn’t. In part, that was because random-digit dialling worked, and other approaches didn’t so much. Almost everyone had exactly one home phone number, so random dialling meant random sampling of households, and most people answered the phone and responded to surveys. On top of that, though, the infrastructure for random-digit dialling was expensive. Installing it showed you were serious about conducting accurate surveys, and demanding it showed you were serious about paying for accurate results.

Today, response rates are much lower, cell-phones are common, links between phone number and geographic location are weaker, and the correspondence between random selection of phones and random selection of potential respondents is more complicated. Random-digit dialling, while still helpful, is much less important to survey accuracy than it used to be. It still has a lot of value as a signalling mechanism, distinguishing Gallup and Pew Research from Honest Joe’s Sample Emporium and website clicky polls.

Signalling is valuable to the signaller and to consumer, but it’s harmful to people trying to innovate. If you’re involved with a serious endeavour in public opinion research that recruits a qualitatively representative panel and then spends its money on modelling rather than on sampling, you’re going to be upset with the spreading of fear, uncertainty, and doubt about opt-in sampling.

If you’re a panel-based survey organisation, the challenge isn’t to maintain your principles and avoid doing bogus polling, it’s to find some new way for consumers to distinguish your serious estimates from other people’s bogus ones. They’re not going to do it by evaluating the quality of your statistical modelling.