Road deaths up

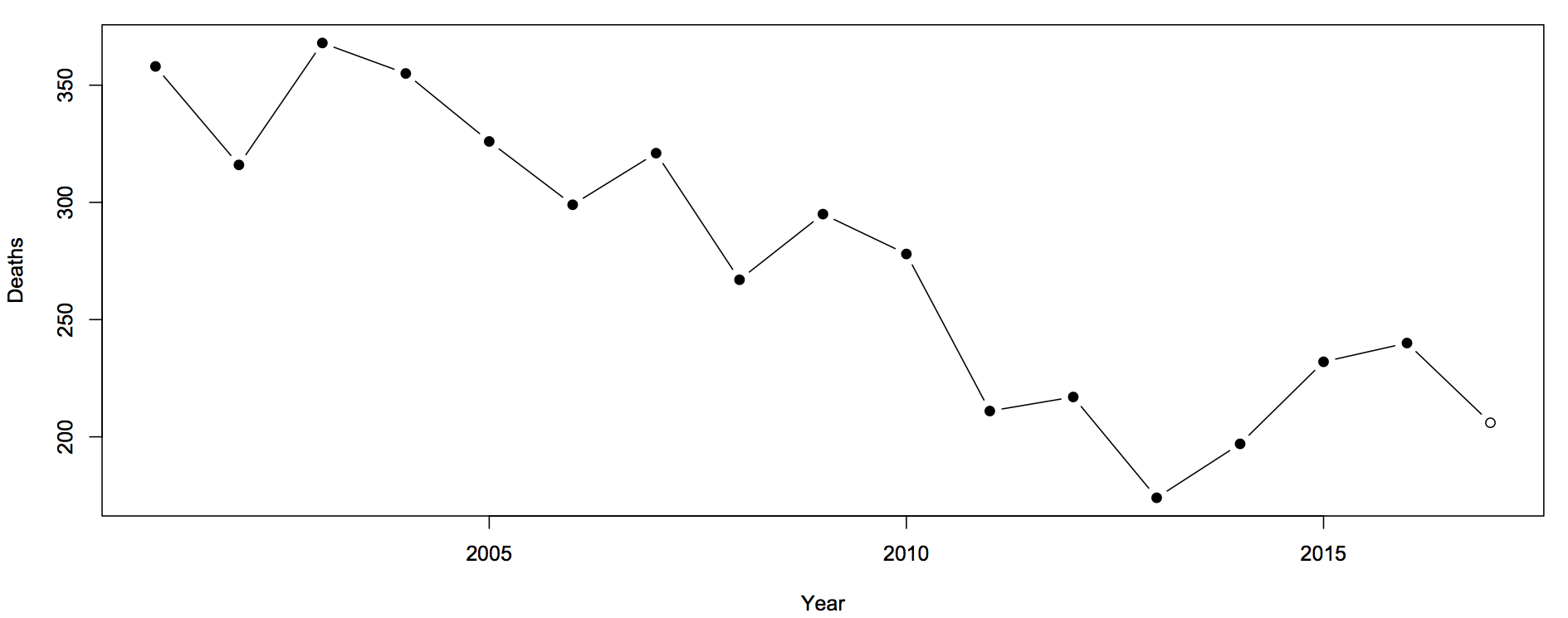

Sam Warburton (the economist, not the rugby player) has been writing about the recent increase in road deaths. Here are the counts (with partial 2017 data)

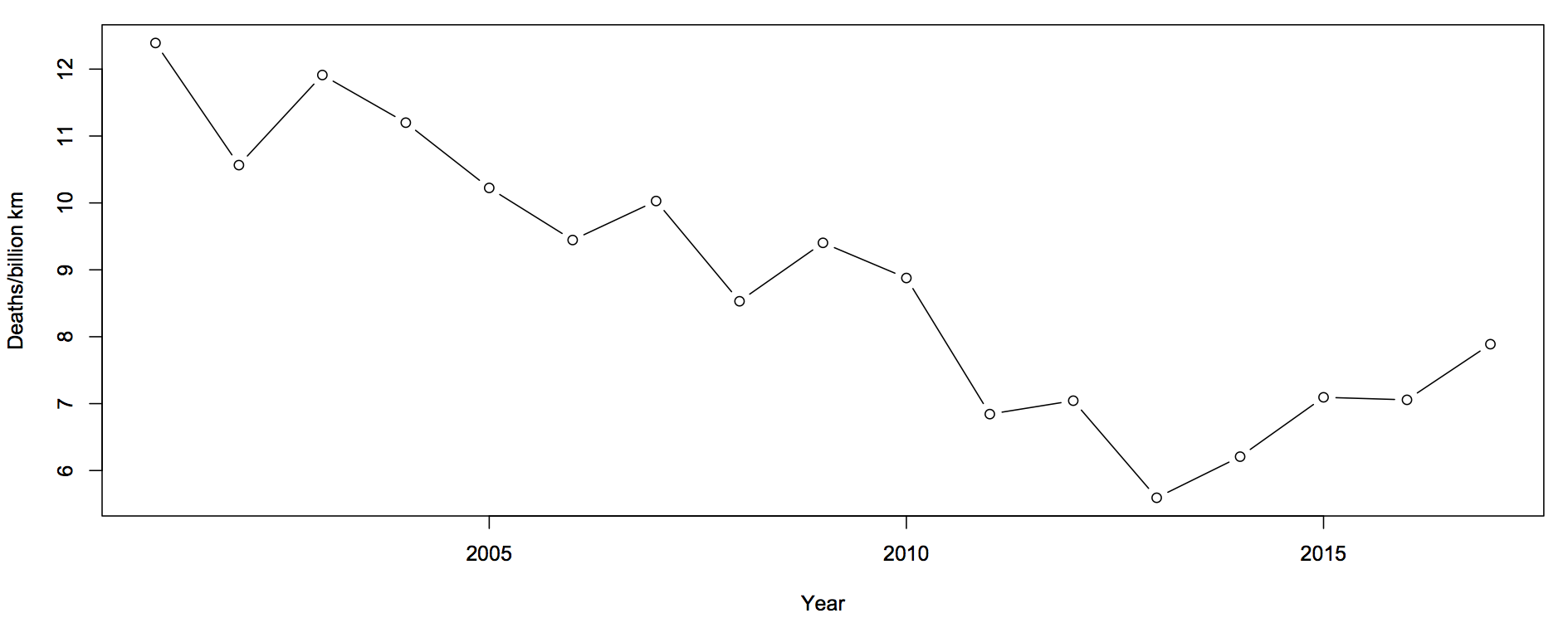

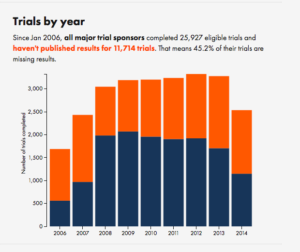

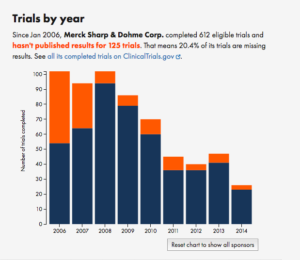

The first question you should ask is whether this is explained by population increases or by driving increases. That is, we want rates — deaths per unit of distance travelled

There’s still an increase, but now the 2017 partial data are in line with the increase. The increase cannot be explained simply by more cars being on the roads.

The next question is about uncertainty. Traditionally, news stories about the road toll were based on one month of data and random variation could explain it all. We still need a model for how much random variation to expect. What I said before was

The simplest mathematical model for counts is the Poisson process. If dying in a car crash is independent for any two people in NZ, and the chance is small for any person (but not necessarily the same for different people) then number of deaths over any specified time period will follow a Poisson distribution. The model cannot be exactly right — multiple fatalities would be much rarer if it were — but it is a good approximation, and any more detailed model would lead to more random variation in the road toll than the Poisson process does.

In that case I was arguing that there wasn’t any real evidence of a change, so using an underestimate of the random variation made my case harder. In this case I’m arguing the change is larger than random variation, so I need to make sure I don’t underestimate random variation.

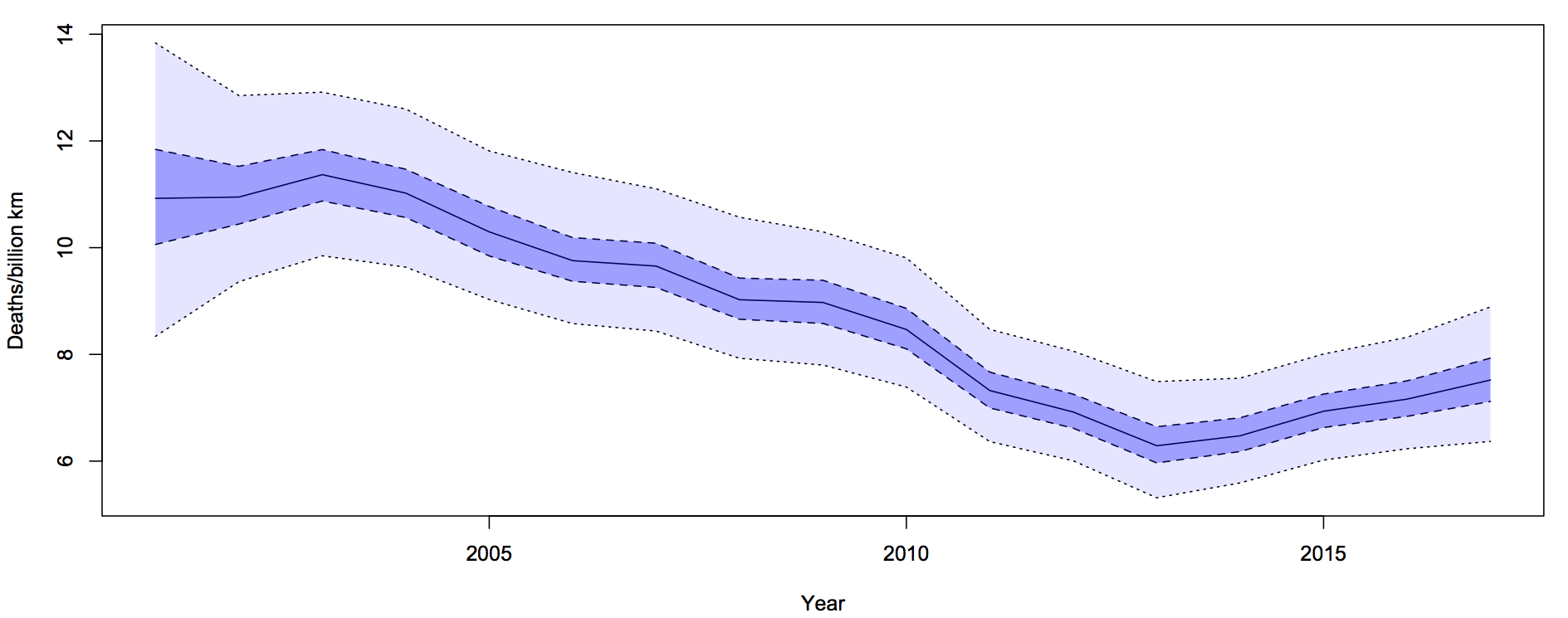

What I did was fit a Bayesian model with two extra random components. The first was the trend over time. To avoid making assumptions about the shape of the trend I just assumed that the difference between adjacent years was relatively small and random. The second random component was a difference between the trend value for a year and the ‘true’ rate for that year. On top of all of that, there’s Poisson variation. Since the size of the two additional random components is estimated from the data, they will capture all the variation.

For each year, there is a 50% probability that the underlying rate is in the darker blue interval, and a 95% probability it’s in the light blue interval. The trend is smoother than the data because the data has both the Poisson variation and the extra year-specific deviation. There’s more uncertainty in 2001 because we didn’t use pre-2001 data to tie it down at all, but that won’t affect the later half of the time period much.

It looks from the graph as though there was a minimum in 2013-14 and an increased rate since then. One of the nice things about these Bayesian models is that you can easily and meaningfully ask for the probability that each year was the minimum. The probability is 54% for 2013 and 27% for 2014: there really was a minimum around then.

The probability that the rate is higher in 2017 than in 2013 is over 90%. This one isn’t just random variation, and it isn’t population increase.

Update: Peter Ellis, who has more experience with NZ official statistics and with Bayesian state-space time series models, gets qualitatively similar results