Screening is harder than that

Calcium in the blood could provide an early warning of certain cancers, especially in men, research has shown.

Even slightly raised blood levels of calcium in men was associated with an increased risk of cancer diagnosis within one year.

The discovery, reported in the British Journal of Cancer, raises the prospect of a simple blood test to aid the early detection of cancer in high risk patients.

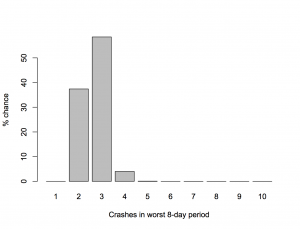

In fact, from the abstract of the research paper, 3% of people had high blood levels of calcium, and among those, 11.5% of the men developed cancer within a year. That’s really not strong enough prediction to be useful for early detection of cancer. For every thousand men tested you would find three cancer cases, and 27 false positives. What the research paper actually says under “Implications for clinical practice” is

“This study should help GPs investigate hypercalcaemia appropriately.”

That is, if a GP happens to measure blood calcium for some reason and notices that it’s abnormally high, cancer is one explanation worth checking out.

The overstatement is from a Bristol University press release, with the lead

High levels of calcium in blood, a condition known as hypercalcaemia, can be used by GPs as an early indication of certain types of cancer, according to a study by researchers from the universities of Bristol and Exeter.

and later on an explanation of why they are pushing this angle

The research is part of the Discovery Programme which aims to transform the diagnosis of cancer and prevent hundreds of unnecessary deaths each year. In partnership with NHS trusts and six Universities, a group of the UK’s leading researchers into primary care cancer diagnostics are working together in a five year programme.

While the story isn’t the Herald’s fault, using a photo of a man drinking a glass of milk is. The story isn’t about dietary calcium being bad, it’s about changes in the internal regulation of calcium levels in the blood, a completely different issue. Milk has nothing to do with it.