- From Felix Salmon: US population is increasing, and people are moving to the cities, so why is (sufficiently fine-scale) population density going down? Because rich people take up more space and fight for stricter zoning. You’ve heard of NIMBYs, but perhaps not of BANANAs

- From the New York Times. One of the big credit-rating companies is no longer using debts referred for collection as an indicator, as long as they end up paid. This isn’t a new spark of moral feeling, it’s just for better prediction.

- And from Felix Salmon again: Firstly, Americans are bad at statistics. When it comes to breast cancer, they massively overestimate the probability that early diagnosis and treatment will lead to a cure, while they also massively underestimate the probability that an undetected cancer will turn out to be harmless.

Posts filed under Random variation (139)

Some surprising things

Screening

Stuff has a story (borrowed from the West Island) headlined “Over 40? Five tests you need right now”.

You might have expected some reference to the other recent news about screening: that the US Preventive Services Taskforce has now joined the Centers for Disease Control in recommending universal screening for HIV (as TVNZ reported). It’s not clear if New Zealand will follow the trend — HIV infection in people not in high risk groups is less common here than in the US, so the benefit compared to more selective screening is smaller here. This illustrates the complexities of population screening. Not only does the test have to be accurate, especially in terms of its false positive rate, but there needs to be something useful you can do about a positive result, and screening everyone has to be better than just screening selected people.

So, let’s compare the suggestions from Stuff’s story to what national and international expert guidelines say you need.

Two of the tests, for high blood pressure and high cholesterol, are spot on. These are part of the national 2012/13 Health Targets for DHBs, with the goal being 75% of the eligible population having the tests within a five-year period. The Health Target also includes blood glucose measurement to diagnose diabetes, which the story doesn’t mention. The US Preventive Services Taskforce also recommends blood pressure and cholesterol tests, though it recommends universal diabetes screening only after age 50 or in people with high blood pressure or people with risk factors for diabetes.

One of the tests recommended in the story is a depression/anxiety questionnaire, for diagnosing suicide risk. Just a couple of weeks ago, the US Preventive Services Taskforce issued guidelines on universal screening for suicide prevention by GPs, saying that there wasn’t good enough evidence to recommend either for or against. As the coverage from Reuters explains, these questionnaires do probably identify people at higher risk of suicide, but it wasn’t clear how much benefit came from identifying them. So, that’s not an unreasonable test to recommend, but it would have been better to indicate that it was controversial.

One more of the tests isn’t a screening test at all — the story recommends that you make sure you know what a standard drink of alcohol is.

The top recommendation in the story, though, is coronary calcium screening. The US Preventive Services Taskforce recommends against coronary calcium screening for people at low risk of heart disease and says there isn’t enough evidence to recommending for or against in people at higher risk for other reasons. The American Heart Association also recommends against routine coronary calcium screening (they say it might be useful as a tiebreaker in people known to be at intermediate risk of heart disease based on other factors). No-one doubts that calcium in the walls of your coronary arteries is predictive of heart disease, but people with high levels of coronary calcium tend to also be overweight or smokers, or have high blood pressure or high cholesterol or diabetes — and if they don’t have these other risk factors it’s not clear that anything can be done to help them.

As an afterthought on the coronary calcium screening point, the story has an additional quote from a doctor recommending coronary angiography before starting a serious exercise program. I’d never heard of coronary angiography as a general screening recommendation — it’s a bit more invasive and higher-risk than most population screening. It turns out that the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association are similarly unenthusiastic, with their guidelines on use specifically recommending against angiography for screening of people without symptoms of coronary artery disease.

Random numbers from a radioactive source

Here’s a fun link which talks about the difference between truly random numbers and pseudo-random numbers. When we teach this, we often mention generation of random numbers (or at least the random number seed) from a radioactive source as one way of getting truly random numbers. Here is someone actually doing it. The sequel is well worth a watch too if you have the time.

Power failure threatens neuroscience

A new research paper with the cheeky title “Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience” has come out in a neuroscience journal. The basic idea isn’t novel, but it’s one of these statistical points that makes your life more difficult (if more productive) when you understand it. Small research studies, as everyone knows, are less likely to detect differences between groups. What is less widely appreciated is that even if a small study sees a difference between groups, it’s more likely not to be real.

The ‘power’ of a statistical test is the probability that you will detect a difference if there really is a difference of the size you are looking for. If the power is 90%, say, then you are pretty sure to see a difference if there is one, and based on standard statistical techniques, pretty sure not to see a difference if there isn’t one. Either way, the results are informative.

Often you can’t afford to do a study with 90% power given the current funding system. If you do a study with low power, and the difference you are looking for really is there, you still have to be pretty lucky to see it — the data have to, by chance, be more favorable to your hypothesis than they should be. But if you’re relying on the data being more favorable to your hypothesis than they should be, you can see a difference even if there isn’t one there.

Combine this with publication bias: if you find what you are looking for, you get enthusiastic and send it off to high-impact research journals. If you don’t see anything, you won’t be as enthusiastic, and the results might well not be published. After all, who is going to want to look at a study that couldn’t have found anything, and didn’t. The result is that we get lots of exciting neuroscience news, often with very pretty pictures, that isn’t true.

The same is true for nutrition: I have a student doing a Honours project looking at replicability (in a large survey database) of the sort of nutrition and health stories that make it to the local papers. So far, as you’d expect, the associations are a lot weaker when you look in a separate data set.

Clinical trials went through this problem a while ago, and while they often have lower power than one would ideally like, there’s at least no way you’re going to run a clinical trial in the modern world without explicitly working out the power.

Other people’s reactions

Gun deaths visualisation

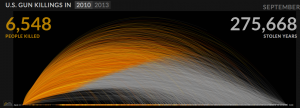

Periscopic, a “socially conscious data visualization firm” has produced an interactive display of the years of life lost due to gun violence in the US, based on national life expectancy data. Each victim appears as a dot moving along the arc of their life, and then dropping at the age of death. More and more accumulate as you watch.

Of course, it’s important to remember that this display gets a lot of its power from two facts: the USA is very big, and we know the names and ages of death of gun victims. You couldn’t do the same thing as dramatically for smoking deaths, and it would look much less impressive in a small country.

Also, Alberto Cairo has a nice post using this as an example to talk about the display of uncertainty.

(via @hildabast)

Briefly

Despite the date, this is not in any way an April Fools post

- “Data is not killing creativity, it’s just changing how we tell stories”, from Techcrunch

- Turning free-form text into journalism: Jacob Harris writes about an investigation into food recalls (nested HTML tables are not an open data format either)

- Green labels look healthier than red labels, from the Washington Post. When I see this sort of research I imagine the marketing experts thinking “how cute, they figured that one out after only four years”

- Frances Woolley debunks the recent stories about how Facebook likes reveal your sexual orientation (with comments from me). It’s amazing how little you get from the quoted 88% accuracy, even if you pretend the input data are meaningful. There are some measures of accuracy that you shouldn’t be allowed to use in press releases.

Confirmation bias

From the Waikato Times, two quotes from a story on emergency services

He would not comment on what motivated the fracas or whether it was gang-related.

“We’re not jumping to conclusions.”

and

Though science dismisses any link between human behaviour and the moon, it’s cold comfort for hospitality staff and emergency workers who say the amount of trouble often spikes when the moon is at its brightest.

Ms Gill said staff reported that “the full moon often has an impact on the nature of presentations through ED”.

Science doesn’t dismiss a link. There’s nothing unscientific about the idea of a link. It’s just that people have looked carefully and it’s not true.

(via @petrajane)

Unclear on the concept: average time to event

One of our current Stat of the Week nominations is a story on Stuff claiming that criminals sentenced to preventive detention are being freed after an average of ‘only’ 11 years.

There’s a widely-linked story in the Guardian claiming that the average time until Google kills new services is 1459 days, based on services that have been cancelled in the past. The story even goes on to say that more recent services have been cancelled more quickly.

As far as I know, no-one has yet produced a headline saying that the average life expectancy for people born in the 21st century is only about 5 years, but the error in reasoning would be the same.

In all three cases, we’re interested in the average time until some event happens, but our data are incomplete, because the event hasn’t happened for everyone. Some Google services are still running; some preventive-detention cases are still in prison; some people born this century are still alive. A little thought reveals that the events which have occurred are a biased sample: they are likely to be the earliest events. The 21st century kids who will live to 90 are still alive; those who have already died are not representative.

In medical statistics, the proper handling of times to death, to recurrence, or to recovery is a routine problem. It’s still not possible to learn as much as you’d like without assumptions that are often unreasonable. The most powerful assumption you can make is that the rate of events is constant over time, in which case the life expectancy is the total observed time divided by the total number of events — you need to count all the observed time, even for the events that haven’t happened yet. That is, to estimate the survival time for Google services, you add up all the time that all the Google services have operated, and divide by the number that have been cancelled. People in the cricket-playing world will recognise this as the computation used for batting averages: total number of runs scored, divided by total number of times out.

The simple estimator is often biased, since the risk of an event may increase or decrease with time. A new Google service might be more at risk than an established one; a prisoner detained for many years might be less likely to be released than a more recent convict. Even so, using it distinguishes people who have paid some attention to the survivors from those who haven’t.

I can’t be bothered chasing down the history of all the Google services, but if we add in search (from 1997), Adwords (from 2000), image search (2001), news (2002), Maps, Analytics, Scholar, Talk, and Transit (2005), and count Gmail only from when it became open to all in 2007, we increase the estimated life expectancy for a Google service from the 4 years quoted in the Guardian to about 6.5 years. Adding in other still-live services can only increase this number.

For a serious question such as the distribution of time in preventive detention you would need to consider trends over time, and differences between criminals, and the simple constant-rate model would not be appropriate. You’d need a bit more data, unless what you wanted was just a headline.

When you have two numbers

Last month, Statistics New Zealand released the travel and migration statistics for January. Visits from China and Hong Kong were notably lower than the past year. This was attributed to Chinese New Year being in February. The media duly reported all this.

Now, Statistics New Zealand has released the travel and migration statistics for January. Visits from China and Hong Kong were notably higher than the past year. This was attributed to Chinese New Year being in February. The media duly reported all this.

It seems obvious that you’d want to combine the two months, so that the Chinese New Year effect drops out. I haven’t seen anyone do this yet:

- Visitors from China: Jan+Feb 2012: 23300+15300=38600

- Vistors from China: Jan+Feb 2013 18800+31500=50300

For Hong Kong the January figures aren’t in the press release, but the change is: there were 2200 more than last year in February, and 1500 fewer in January, for an increase of 700.

So, a fairly big increase in visitors from these countries over the past two years.

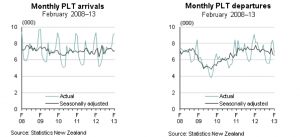

Net migration was also up a bit, and here I think a longer time series than the media reported would be useful. The full time series in the Stats NZ release looks like

Arrivals are pretty constant. Departures are slowly declining, but are still much higher than in the 09/10 minimum.