Not so much poor and huddled masses

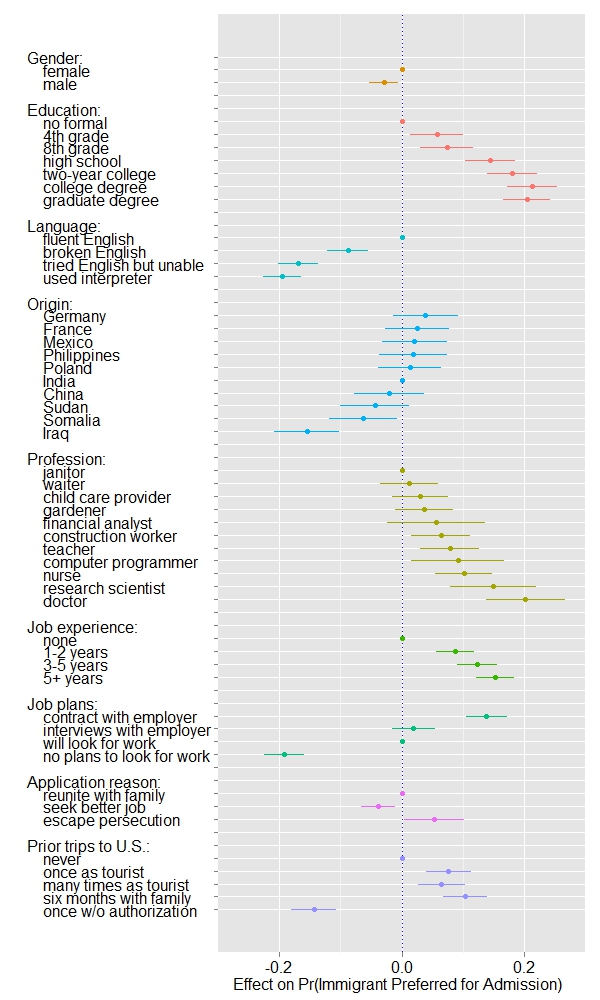

Nice presentation of interesting results on US opinions of immigration. Participants were given two hypothetical immigrants with characteristics chosen from these options, and asked which one they would prefer to admit, and regression models were then used to estimate the impact of each characteristic. Country of origin had a surprisingly small impact; otherwise it was pretty much what you might expect. The story has more details, including a comparison by political affiliation, which reveals almost no disagreement.

While on the topic, you should read Eric Crampton’s proposal that anyone completing a (sufficiently real) degree in NZ should be eligible for permanent residence: not only boosting our education export industry, but attracting young, ambitious, educated immigrants. I think it’s a good idea, but I’m obviously biased.