The Herald has a headline “Quarter of psychosis cases linked to ‘skunk’ cannabis”, saying

People who smoke super-strength cannabis are three times more likely to develop psychosis than people who have never tried the drug – and five times more likely if they smoke it every day.

The relative risks are surprisingly large, but could be true; the “quarter” attributable fraction needs to be qualified substantially. As the abstract of the research paper (PDF) says, in the convenient ‘Interpretation’ section

Interpretation The ready availability of high potency cannabis in south London might have resulted in a greater proportion of first onset psychosis cases being attributed to cannabis use than in previous studies

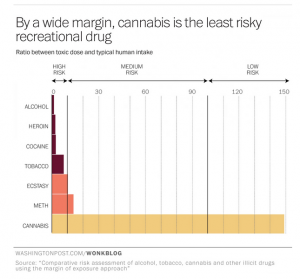

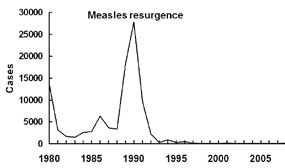

Let’s unpack that a little. The basic theory is that some modern cannabis is very high in THC and low in cannabidiol, and that this is more dangerous than more traditional pot. That is, the ‘skunk’ cannabis has a less extreme version of the same problem as the synthetic imitations now banned in NZ.

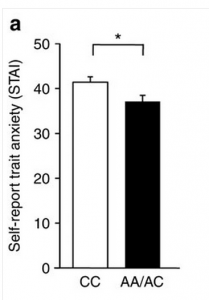

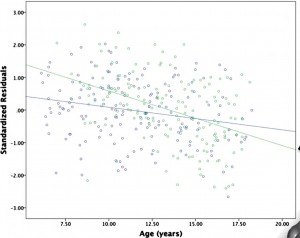

The study compared people admitted as inpatients in a particular area of London (analogous to our DHBs) to people recruited by internet and train advertisements, and leaflets (which, of course, didn’t mention that the study was about cannabis). The control people weren’t all that well matched to the psychosis cases, but it wasn’t too bad. The psychosis cases were somewhat more likely to smoke cannabis, and much more likely to smoke the high-THC type. In fact, smoking of other cannabis wasn’t much different between cases and controls.

That’s where the relative risks of 3 and 5 come from. It’s still possible that these are due at least in part to some other factor; you can’t tell from just this sort of data. The atttributable fraction (a quarter of cases) comes from combining the relative risk with the proportion of the population who are exposed.

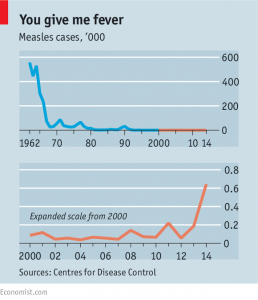

Suppose ‘skunk-type’ cannabis triples your risk, and 20% of people in the population use it, as was seen for controls in the sample. General UK data (eg) suggest the rate in non-users might be 5 cases per 10,000 people per year. So, in 100,000 people, 80,000 would be non-users and you’d expect 40 cases per year. The other 20,000 would be users, and you’d expect a background rate of 10 cases plus 20 extra cases caused by the cannabis. So, in the 100,000 people, you’d get 70 cases per year, 50 of which would have happened anyway and 20 due to cannabis. That’s not exactly the calculation the researchers did — they used a trick where they don’t need the background rate as long as it’s low, and I rounded more — but it’s basically the same. I get 28%; they got 24%.

The figures illustrate two things. First, the absolute risk increase is roughly 20 cases per 100,000 20,000 people per year. Second, the ‘quarter’ estimate is very sensitive to the proportion exposed. If 5% of people used ‘skunk-type’ cannabis, you can run the numbers again and you get 5 cases due to cannabis out of 55 in 100,000 people: only 9% of cases due to exposure.

Now we’re at the ‘interpretation’ quote from the research paper. In this South London area, 20% of people have used mostly the high-potency cannabis and 44% mostly have used other types, with 37% non-users. That’s a lot of pot. Even if the relative risks are correct, the population attributable proportion will be much lower for the UK as a whole (or for NZ as a whole).

Still, the research does tend to support the idea of regulated legalisation, the sort of thing that Mark Kleiman advocates, where limits on THC and/or higher taxes for higher concentrations can be used to push cannabis supply to lower-risk varieties.