There’s a recent paper from Denmark finding that women, particularly young women, who used hormonal contraceptives were more likely also to be diagnosed with depression. The Guardian has a sensible story reporting on the paper (though given the topic it’s a pity the external experts they talked to were both men). There’s also an opinion piece, which conveys the importance of the issue but is clearly written by someone whose opinions were decided before the research came out. I was asked on Twitter what I thought.

One of the more difficult cases for science communication is where the evidence is neither negligible nor overwhelming, and that’s the situation here. There’s nothing intrinsically unlikely about an effect on depression, and there are some ways that this study is very good, but there are also some limitations to the data that make the evidence weaker.

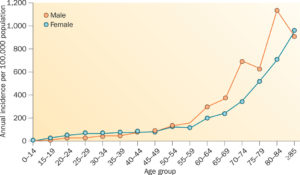

First, the good points. The study involved the entire Danish population over nearly 20 years, meaning that it was large enough to be fairly reliable on whether correlations are present or not, and also that it was comprehensive — it didn’t miss people out. The data on who used hormonal contraceptives comes from the national health system and so should be accurate. The two definitions of depression — ‘prescribed anti-depressant drugs’ and ‘psychiatrist diagnosis of depression’ — will be measured reliably, and the decisions will have been taken by people who don’t have any particular view on the study question. There’s information on timing, so we know the contraceptives were used before the depression. The associations are strong enough to care about, but not so strong as to be implausible. The analysis is well done given the data.

However, there are at least two alternative explanations for the correlation that aren’t ruled out by these data. The first is that the depression definitions require seeing a doctor and asking for (or at least accepting) treatment, and women who take hormonal contraceptives are probably more likely to see a doctor regularly. The second explanation, which the researchers do consider, is that break-ups of relationships are a cause of depression, especially in younger people, and being in these relationships might be related to using hormonal contraceptives. The researchers don’t believe this explanation, and they may be right, but their data don’t rule it out.

It’s not that either of these explanations is necessarily more likely than a direct effect of hormones, but if there weren’t alternative explanations the evidence would be stronger. For example, if the researchers had been able to compare women using hormonal contraceptives just to those using non-hormonal contraceptives (eg copper IUDs and condoms), and had still seen the same correlation, the second explanation would be much less plausible and the evidence for a direct effect would be more convincing.

Also, if there were a straightforward hormonal explanation I would have expected different types of contraceptive to have stronger or weaker associations according to the dose of, say, progestins. In fact what they saw is that less commonly used contraceptives had stronger associations: weakest for the combined pills, stronger for progestin-only ‘mini-pills’ and stronger still for patch and implant methods. Again, this certainly doesn’t rule out a direct effect, but it weakens the evidence.

If a similar study were done in another country with different patterns of contraceptive use and found similar results, the evidence would become stronger. A study with fewer women but more detailed information on mental and emotional health — such as one of the birth-cohort studies — might be able to say more about what leads up to episodes of depression in young women and might be able to say something about who is at most risk. There’s still going to be uncertainty.

So. It’s hard to say for sure. There is definitely some evidence that hormonal contraceptives increase the risk of depression. If the effect is real, it’s useful to know that it seems to be largely in women under 20, largely in the first year of use, and might be worse for the ‘mini-pill’ than the traditional pill. There’s a lot already known — good and bad — about hormonal contraceptives, but this research paper does add something.