There’s a story in the Herald about the impact of changes in the drinking age. It’s a refreshing change since it’s a sensible analysis of reasonable data to address an interesting question; but I still want to disagree with some of the interpretation.

As those of you who have lived in NZ for longer will remember, the drinking age was lowered from 20 to 18 on December 1, 1999. One of the public-health questions this raises is the effect on driving. You’d expect an increase in crashes in 18-20 year olds, but it’s not obvious what would happen in older drivers. You could imagine a range of possibilities:

- People are more at risk when they’re learning to manage drinking in the context of needing to drive, but there’s no real difference between doing this at 18 or at 20

- At eighteen, a significant minority of people still have the street smarts of a lemming and so the problem will be worse than at twenty

- At eighteen, fewer people are driving, so the problem will be less bad

- At eighteen, fewer people are driving so there’s more pressure on those with cars to drive, so the problem will be worse

- At eighteen, drivers are less experienced and are relying more on their reflexes, so the problem will be worse.

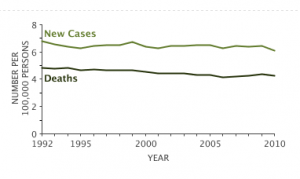

Data would be helpful, and the research (PDF,$; update: now embedded in the story) is about the relative frequency of serious crashes involving alcohol at various ages for 1994-1999, 2000-2004, 2006-2010, ie, before the change, immediately after the change, and when things had settled down a bit. The analysis uses the ratio of crashes involving alcohol to other crashes, to try to adjust for other changes over the period. That’s sensible but not perfect: changing the drinking age could end up changing the average number of passengers per car and affecting the risk that way, for example.

The research found that 18-20 year olds were at 11% lower risk than 20-24 year olds when 20 was the drinking age, and 21% higher risk when 18 was the drinking age (with large margins of uncertainty). That seems to fit the first explanation: there’s a training period when you’re less safe, but it doesn’t make a lot of difference when it happens — the 20% increase for two years matches the 11% increase for four years quite closely. We certainly can’t rule out the problem being worse at 18 than at 20, but there doesn’t seem to be a strong signal that way.

The other thing to note is that the research also looked at fatal crashes separately and there was no real sign of the same pattern being present. That could easily just be because of the sparser data, but it seems worth pointing out given that all three of the young people named in the story were in fatal crashes.