Pharmac rebates

There’s an ‘interactive’ at Stuff about the drug rebates that Pharmac negotiates. The most obvious issue with it is the graphics, for example

and

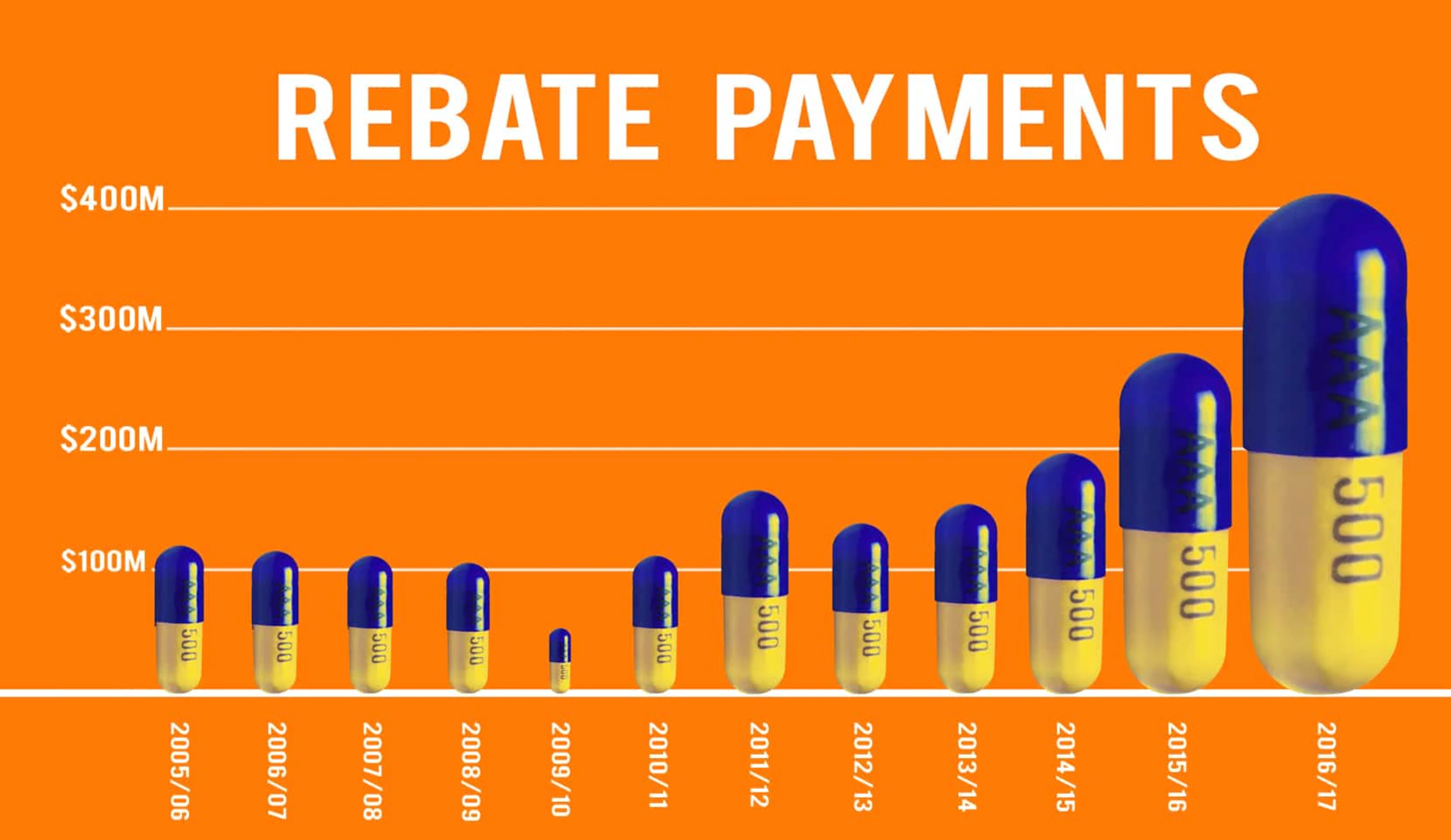

The first of these is a really dramatic illustration of a well-known way graphs can mislead: using just one dimension of a two-dimensional or three-dimensional thing to represent a number. The 2016/7 capsule looks much more than twice as big as the puny little 2014/15 one, because it’s twice as high and twice as wide (and by implication from shading, twice as deep). The first graph also commits the accounting sin of displaying a trend from total, nominal expenditures rather than real (ie, inflation-adjusted) per-capita expenditures.

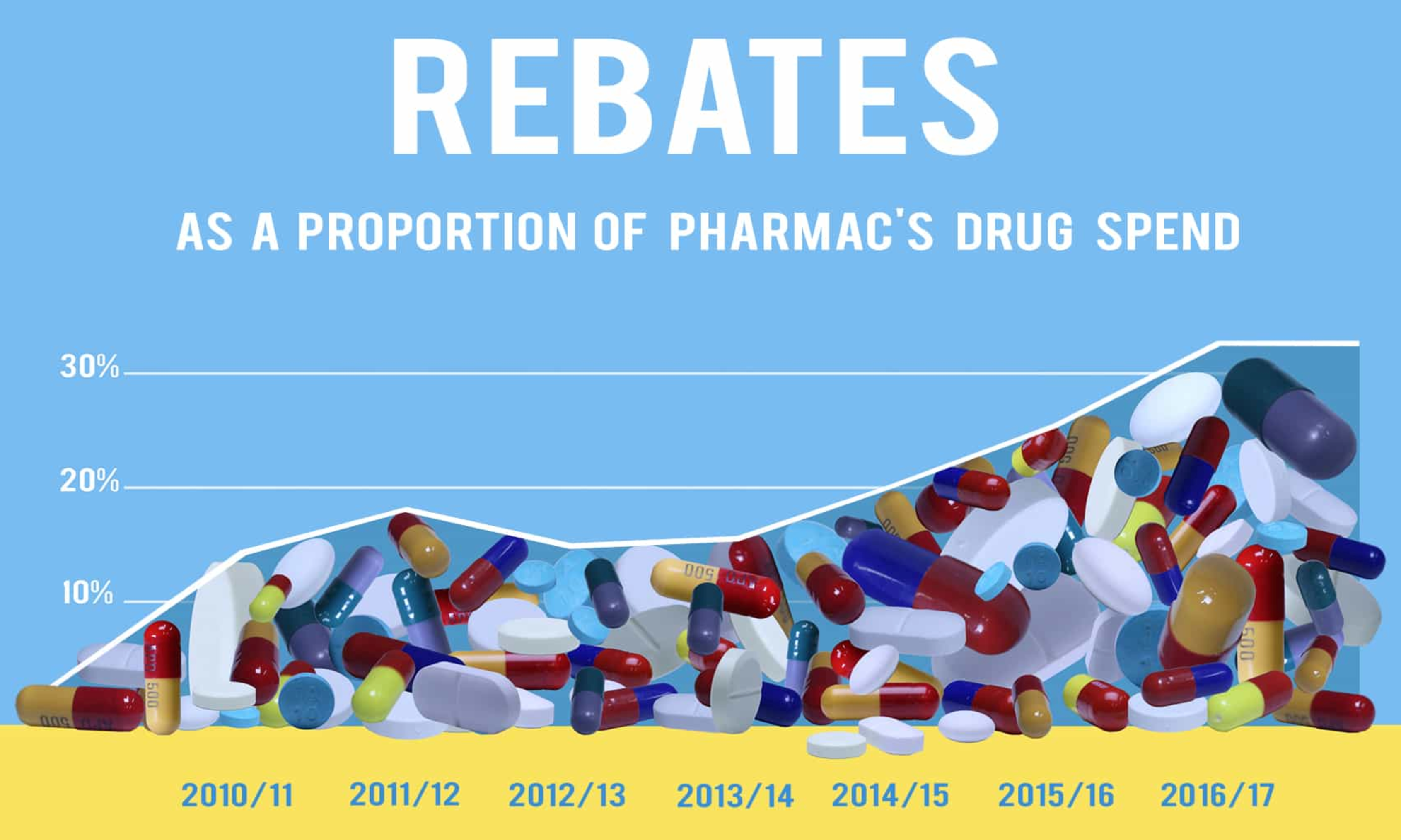

The second one is not as bad, but the descending line to the left of the data points is a bit dodgy, as is the fact that the x-axis is different from the first graph even though the information should all be available. Also, given that rebates are precisely not a component of Pharmac’s drug spend, the percentage is a bit ambiguous. The graph shows total rebates divided by what would have been Pharmac’s “drug spend” in the improbable scenario that the same drugs had been bought without rebates. That is, in the most recent year, Pharmac spent $849 million on drugs. If rebates were $400m as shown in the first graph, the percentage in the second graph is something like ($400 million)/($400 million+$849 million)=32%.

More striking when you listen to the whole thing, though, is how negative it is about New Zealand getting these non-public discounts on expensive drugs. In particular, the primary issue raised is whether we’re getting better or worse discounts than other countries (which, indeed, we don’t know), rather than whether we’re getting good value for what we pay — which we basically do know, because that’s exactly what Pharmac assesses.

Now, since the drug companies do want to keep their prices secret there must be some financial advantage to them in doing so, thus there is probably some financial disadvantage to someone other than them. It’s possible that we’re in that group; that other comparable countries are getting better prices than we are. It’s also possible that we’re getting better prices than them. Given Pharmac’s relatively small budget and their demonstrated and unusual willingness not to subsidise overpriced new drugs, I know which way I’d guess.

There are two refreshing aspects to the interactive, though. First, it’s good to see explicit consideration of the fact that drug prices are primarily not a rich-country problem. Second, it’s good to see something in the NZ mass media in favour of the principle that Pharmac can and should walk away from bad offers. That’s a definite change from most coverage of new miracle drugs and Pharmac.