A number of my colleagues have sent me this link from British newspaper The Guardian, and asked me to comment. In some sense I have done this. I am a signatory to an editorial published in the journal Science and Justice which protests the law lords’ ruling.

The Guardian article refers to a Court of Appeal ruling in the United Kingdom referred to as R v T. The original charge against Mr. T. is that of murder and, given the successful appeal, his name is suppressed. The nature of the appeal relates to whether an expert is permitted to use likelihood ratios in provision of evaluative opinion, whether an evaluative opinion based on an expert’s experience is permissible, and whether it is necessary for an expert to set out in a report the factors on which evaluative opinion based.

It is worthwhile noting before we proceed that to judge a case solely on one aspect of the whole trial is dangerous. Most trials are complex affairs with many pieces of evidence, and much more testimony that the small aspects we concentrate on here.

The issue of concern to members of the forensic community is the following part of the ruling:

In the light of the strong criticism by this court in the 1990s of using Bayes theorem before the jury in cases where there was no reliable statistical evidence, the practice of using a Bayesian approach and likelihood ratios to formulate opinions placed before a jury without that process being disclosed and debated in court is contrary to principles of open justice.

The practice of using likelihood ratios was justified as producing “balance, logic, robustness and transparency”, as we have set out at [54]. In our view, their use in this case was plainly not transparent. Although it was Mr Ryder’s evidence (which we accept), that he arrived at his opinion through experience, it would be difficult to see how an opinion of footwear marks arrived at through the application of a formula could be described as “logical”, or “balanced” or “robust”, when the data are as uncertain as we have set out and could produce such different results.

A Bayesian, or likelihood ratio (LR) approach to evidence interpretation, is a mathematical embodiment of three principles of evidence interpretation given by Ian Evett and Bruce Weir in their book Interpreting DNA Evidence: Statistical Genetics for Forensic Scientist. Sinauer, Sunderland, MA 1998. These principles are

- To evaluate the uncertainty of any given proposition it is necessary to consider at least one alternative proposition

- Scientific interpretation is based on questions of the kind “What is the probability of the evidence given the proposition?”

- Scientific interpretation is conditioned not only by the competing propositions, but also by the framework of circumstances within which they are to be evaluated

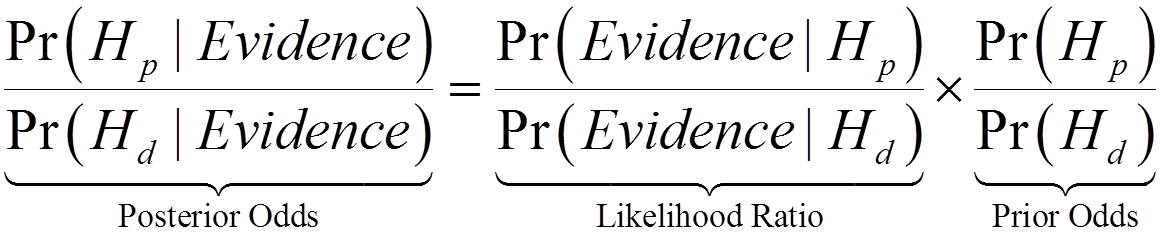

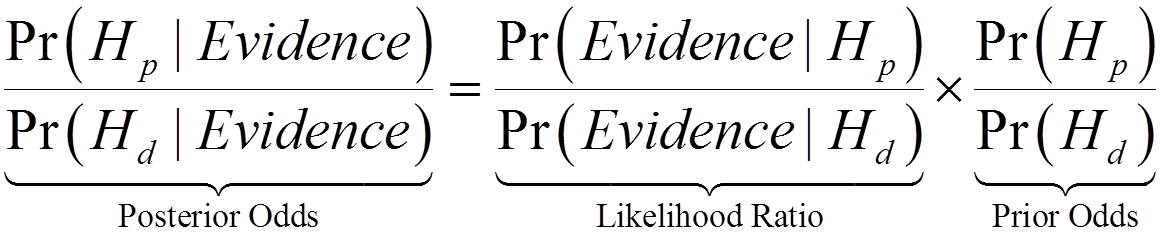

The likelihood ratio is the central part of the odds form of Bayes’ Theorem. That is

The likelihood ratio gives the ratio of the probability of the evidence given the prosecution hypothesis to the probability of the evidence given the defense hypothesis. It is favoured by members of my community because it allows the expert to comment solely on the evidence, which is all the court has asked her or him to do.

The basis for the appeal in R v T was that the forensic scientist, Mr Ryder, in the first instance computed a likelihood ratio, but did not explicitly tell the court he had done so. In the second instance, there was also criticism that the data needed to evaluate the LR was not available.

Mr Ryder considered four factors in his evaluation of the evidence. These were the pattern, the size, the wear and the damage.

The sole pattern is usually the most obvious feature of a shoe mark or impression. Patterns are generally distinct between manufacturers and to a lesser extent between different shoes that a manufacturer makes. Mr Ryder considered the probability of the evidence (the fact that the shoe impression “matches” the impression left by the defendant’s shoe) if it indeed was his shoe that left it. It is reasonable to assume that this probability is one or close to one. If the defendant’s shoe did not leave the mark, then we need a way of evaluating the probability of a “adventitious” match. That is, what’s the chance that the defendant’s shoe just happened to match by sheer bad luck alone? A reasonable estimate of this probability is the frequency of the pattern in the relevant population. Mr Ryder used a database of shoe pattern impressions found at crime scenes. Given that this mark was found at a crime scene this seems a reasonable population to consider. In this database the pattern was very common with a frequency of 0.2. The defense made much stock of the fact that the database represented only a tiny fraction of the shoes produced in the UK in a year (0.00006 per cent), and therefore it was not comprehensive enough to make the evaluation. In fact, the defense had done its own calculation which was much more damning for their client. Using the 0.2 frequency gives a LR of 5. That is, the evidence is 5 times more likely if Mr T.’s shoe left the mark rather than a shoe of a random member of the population.

The shoe size is also a commonly used feature in footwear examination. The shoe impression was judged to be size 11. Again the probability of the evidence if Mr T.’s shoe left the mark was judged to be one. It is hard to work out exactly what Mr Ryder did from the ruling, because a ruling is the judges’ recollection of proceedings, which is not actually an accurate record of what may, or may not, have been said. According to the ruling, Mr Ryder used a different database to assess the frequency of size. He estimated this to be 3%. The judges incorrectly equate this to 0.333, instead of 0.03 which would lead to an LR of 33.3. Mr Ryder used a “more conservative” figure to reflect to some uncertainty in size determination to 0.1, giving an LR of 10.

Wear on shoes can be different between different people. Take a look at the soles of your shoes and those of a friend. They will probably be different. To evaluate the LR, Mr Ryder considered that the wear on the trainers. He felt could exclude half of the trainers of this pattern type and approximate size/configuration. He therefore calculated the likelihood ratio for wear as 1/0.5 or 2. Note here that Mr Ryder appears to have calculated the probability of wear given pattern and size.

Finally, Mr Ryder considered the damage to the shoes. Little nicks and cuts accumulate on shoes over time and can be quite distinctive. Mr Ryder felt he could exclude very few pairs of shoes that could not previously have been excluded by the other factors. That is the defendant’s shoes were no more, or less, likely to have left the mark than any other pair in the database that had the same pattern, size and wear features. Therefore therefore calculated the likelihood ratio for damage as 1.

The overall LR was calculated by multiplying the four LRs together. This is acceptable if either the features were independent, or the appropriate conditional probabilities were considered. This multiplication gave an LR of 100, and that figure was converted using a “verbal scale” into the statement “the evidence provides moderate support for the proposition that the defendant’s shoe left the mark.” Verbal scales are used by many forensic agencies who employ an LR approach because they are “more easily understood” by the jury and the court.

The appeal judges ruled that this statement, without the explicit inclusion of information explaining that it was based on an LR, was misleading. Furthermore, they ruled that the data used to calculate the LR was insufficient. I, and many of my colleagues, disagree with this conclusion.

So what are the consequences of this ruling? It remains to be seen. In the first instance I think it will be an opening shot for many defense cases in the same way that they try to take down the LR because it is “based on biased Bayesian reasoning.” I do think that it will force forensic agencies to be more open about their calculations, but I might add that Mr Ryder didn’t seek to conceal anything from the court. He was simply following the guidelines set out by the Association of Footwear, Tool marks, and Firearms Examiners guidelines.

It would be very foolish of the courts to dismiss the Bayesian approach. After all, Bayes’ Theorem simply says (in mathematical notation) that you should update your belief about the hypotheses based on the evidence. No judge would argue that against that.