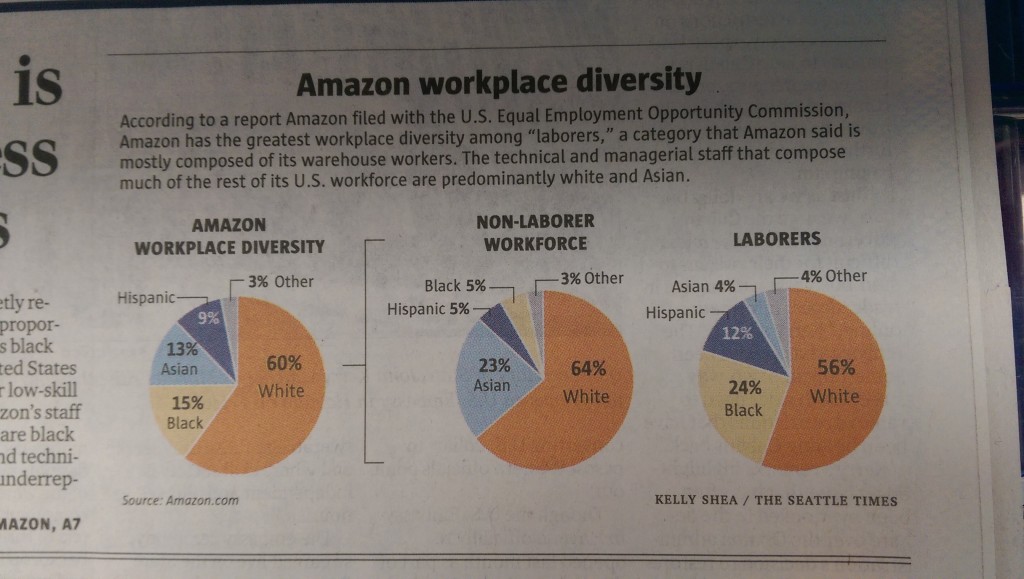

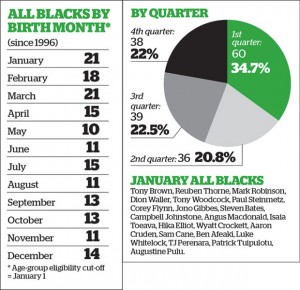

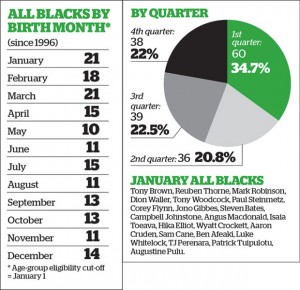

This graphic and the accompanying story in the Herald produced a certain amount of skeptical discussion on Twitter today.

It looks a bit as though there is an effect of birth month, and the Herald backs this up with citations to Malcolm Gladwell on ice hockey.

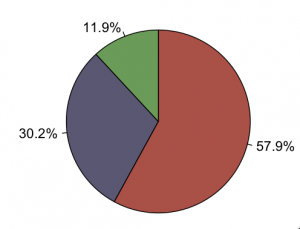

The first question is whether there is any real evidence of a pattern. There is, though it’s not overwhelming. If you did this for random sets of 173 people, about 1 in 80 times there would be 60 or more in the same quarter (and yes, I did use actual birth frequencies rather than just treating all quarters as equal). The story also looks at the Black Caps, where evidence is a lot weaker because the numbers are smaller.

On the other hand, we are comparing to a pre-existing hypothesis here. If you asked whether the data were a better fit to equal distribution over quarters or to Gladwell’s ice-hockey statistic of a majority in the first quarter, they are a much better fit to equal distribution over quarters.

The next step is to go slightly further than Gladwell, who is not (to put it mildly) a primary source. The fact that he says there is a study showing X is good evidence that there is a study showing X, but it isn’t terribly good evidence that X is true. His books are written to communicate an idea, not to provide balanced reporting or scientific reference. The hockey analysis he quotes was the first study of the topic, not the last word.

It turns out that even for ice-hockey things are more complicated

Using publically available data of hockey players from 2000–2009, we find that the relative age effect, as described by Nolan and Howell (2010) and Gladwell (2008), is moderate for the average Canadian National Hockey League player and reverses when examining the most elite professional players (i.e. All-Star and Olympic Team rosters).

So, if you expect the ice-hockey phenomenon to show up in New Zealand, the ‘most elite professional players’, the All Blacks might be the wrong place to look.

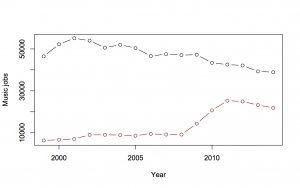

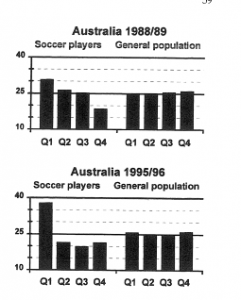

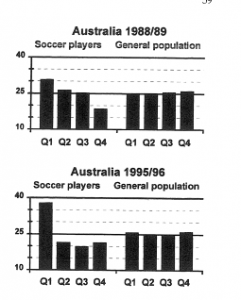

On the other hand Rugby League in the UK does show very strong relative age effects even into the national teams — more like the 50% in first quarter that Gladwell quotes for ice hockey. Further evidence that things are more complicated comes from soccer. A paper (PDF) looking at junior and professional soccer found imbalances in date of birth, again getting weaker at higher levels. They also had an interesting natural experiment when the eligibility date changed in Australia, from January 1 to August 1.

As the graph shows, the change in eligibility date was followed by a change in birth-date distribution, but not how you might expect. An August 1 cutoff saw a stronger first-quarter peak than the January 1 cutoff.

Overall, it really does seem to be true that relative age effects have an impact on junior sports participation, and possibly even high-level professional acheivement. You still might not expect the ‘majority born in the first quarter’ effect to translate from the NHL as a whole to the All Blacks, and the data suggest it doesn’t.

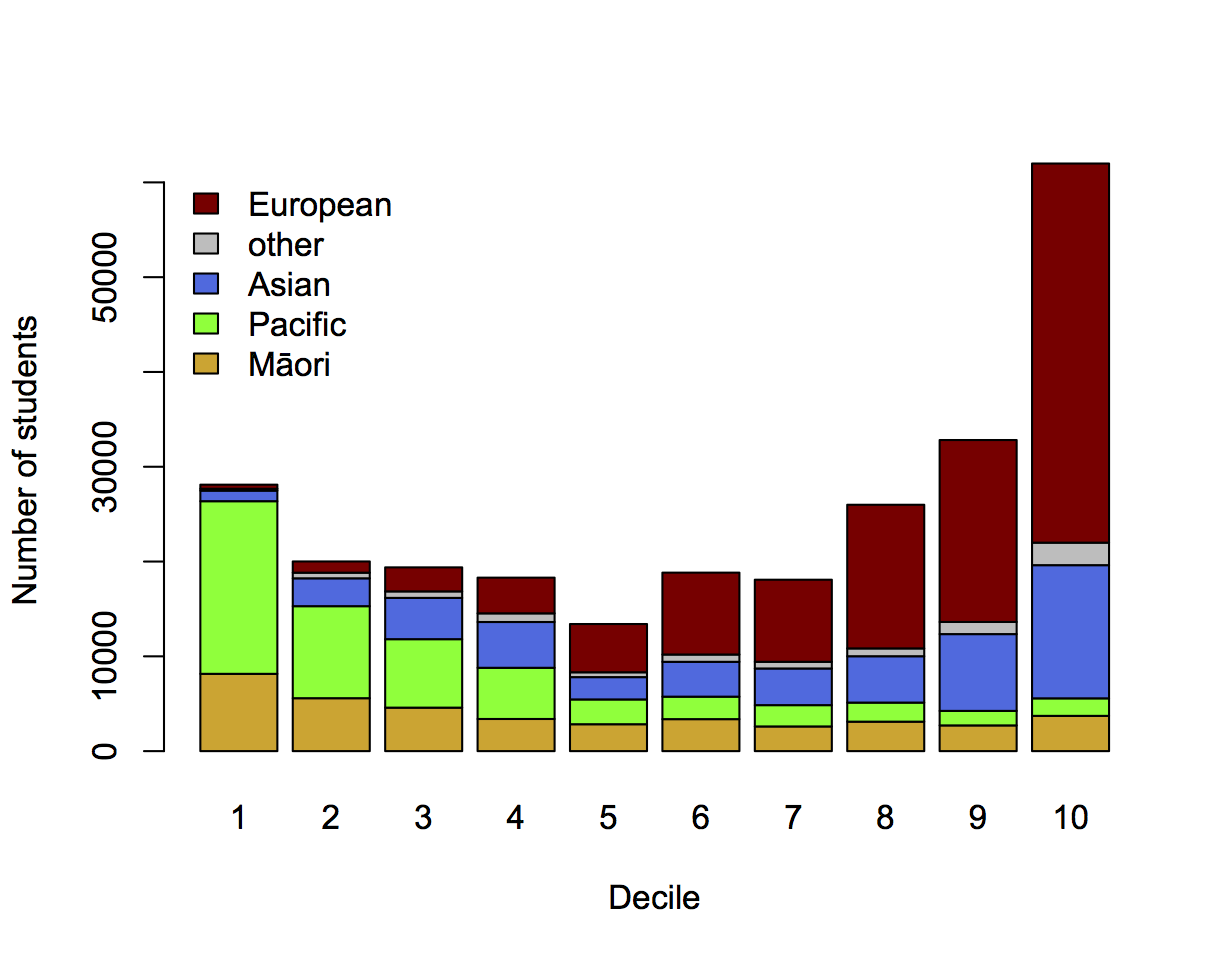

Rather more important, however, are relative age effects in education. After all, there’s a roughly 99.9% chance that your child isn’t going to be an All Black, but education is pretty much inevitable. There’s similar evidence that the school-age cutoff has an effect on educational attainment, which is weaker than the sports effects, but impacts a lot more people. In Britain, where the school cutoff is September 1:

Analysis shows that approximately 6% fewer August-born children reached the expected level of attainment in the 3 core subjects at GCSE (English, mathematics and science) relative to September-born children (August born girls 55%; boys 44%; September born girls 61% boys 50%)

In New Zealand, with a March 1 cutoff, you’d expect worse average school performance for kids born on the dates the Herald story is recommending.

As with future All Blacks, the real issue here isn’t when to conceive. The real issue is that the system isn’t working as well for some people. The All Blacks (or more likely the Blues) might play better if they weren’t missing key players born in the wrong month. The education system, at least in the UK, would work better if it taught all children as well as it teaches those born in autumn. One of these matters.