Population density: drawing the lines

David Seymour, on the Herald website

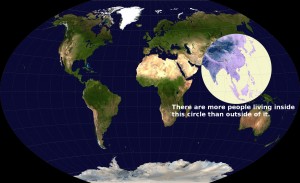

Auckland is already denser than New York, and most American and Australian cities. The 1.6 million people in Manhattan may live cheek-by-jowl, but not the other 20 million inhabiting the wider urban area.

An intelligent politician wouldn’t say something as apparently bizarre as this first sentence if it wasn’t true, so of course it is. The question is going to be true in what sense?

Based on the population figure, Mr Seymour is talking about the New York Metropolitan Statistical Area, aka, New York Urban Area, which has a population of 20.1 million and a population density of 724/km2[*]. The Auckland Urban Area has a population of 1.45 million and a density of 2,600/km2, and, yes, 2600 is larger than 724. However, as the scenic photos in the Wikipedia page for the New York Metropolitan Area suggest, that might not be a fair comparison.

In fact, it’s true almost by definition that the New York metropolitan area has a lower density than urban Auckland

Urban areas in the United States are defined by the U.S. Census Bureau as contiguous census block groups with a population density of at least 1,000/sq mi (390/km2) with any census block groups around this core having a density of at least 500/sq mi (190/km2). [Wikipedia, or see full legal definition]

That is, the metropolitan area is defined as the area around New York City all the way out until the local population density is below 190/km2. It’s a sensible statistical unit — the US Census Bureau wasn’t trying to make a political point about urban infill when they defined it — but it’s not the same sort of unit as Stats New Zealand’s definition of urban or metro Auckland.

So, what other comparisons could we do? We could compare the New York Metropolitan Area to the Auckland Supercity, whose population density of 320/km2 is less than half as high. That might be unfair in the other direction — the Supercity is designed with the future expansion of Auckland in mind, while the US definitions are only intended for a ten-year period between censuses.

We can’t quite do the perfect comparison of redrawing Auckland Urban Area by the US rules, because NZ Area Units are bigger than US Census Block Groups, and NZ meshblocks are smaller, but someone with more time than me could try.

We could compare the Auckland urban area to genuinely urban parts of the New York metro: Mr Seymour mentioned Manhattan (density 27,673/km2, three times that of the Auckland CBD, nine times that of the Epsom electorate) but the other four boroughs of New York City all have higher density than urban Auckland. Two of them (the Bronx, and Brooklyn) have higher density than the Auckland CBD, Queens (8237/km2) is closer in density to the Auckland CBD than to the rest of Auckland, and even Staten Island is denser than urban Auckland as a whole. In the metropolitan area but across the river from New York City proper we have Hudson County (density 5,241/km2) and Newark (density about 4500/km2). The whole of Long Island, part of the New York metropolitan area, but also known for places like Fire Island and the Hamptons, has population density 2,151/km2, not far below urban Auckland.

And finally, an alternative way to do this whole comparison, which is much less sensitive to where the lines are drawn, is to look at population-weighted densities. That is, for the average person in a city, how dense is the population near them? For the whole New York metropolitan area the population-weighted density is 12000/km2 (or 120/hectare). For Auckland it is 43/hectare. In other words, while people near the edges of the New York metro area have a lot of space, most New Yorkers don’t. The average person in the broad New York metropolitan area sees three times the local population density of the average Aucklander.

Update: * Mr Seymour tells me he was referring the the definition of metropolitan areas from Demographia, which trims some of the low-density parts of the Census Bureau definition of New York to give a population density of 1800, and agrees well with the StatsNZ definition of urban Auckland. So, while the issue about the difficult in defining things comparably is still an issue, it is less his fault than I had assumed.