Surprises in data

When you get access to some data, a first step is to see if you understand it: do the variables measure what you expect, are there surprising values, and so on. Often, you will be surprised by some of the results. Almost always this is because the data mean something a bit different from what you expected. Sometimes there are errors. Occasionally there is outright fraud.

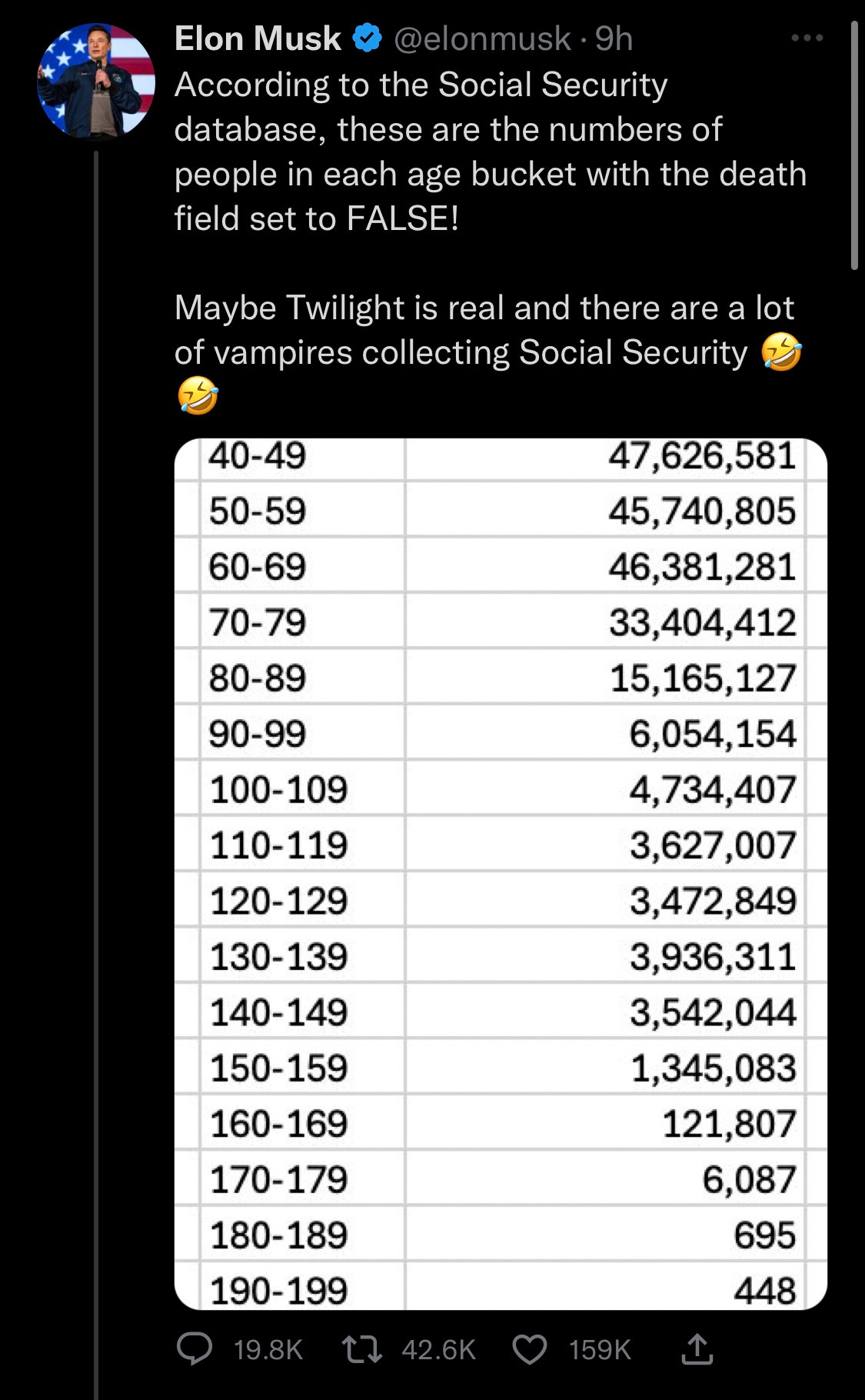

Elon Musk and DOG-E have been looking at US Social Security data. They created a table of Social Security-eligible people not recorded as dead and noticed that (a) some of them were surprisingly old, and (b) the total added up to more than the US population.

That’s a good first step, as I said. The next step is to think about possible explanations (as Dan Davies says: “if you don’t make predictions, you won’t know when to be surprised”). The first two I thought of were people leaving the US after working long enough to be eligible for Social Security (like, for example, me) and missing death records for old people (the vital statistics records weren’t as good in the 19th century as they are now).

After that, the proper procedure is to ask someone or look for some documentation, rather than just to go with your first guess. It’s quite likely that someone else has already observed the existence of records with unreasonable ages and looked for an explanation.

In this case, one would find (eg, by following economist Justin Wolfers) a 2023 report “Numberholders Age 100 or Older Who Did Not Have Death Information on the Numident” (PDF), a report by the Office of the Inspector General, which said that the very elderly ‘vampires collecting Social Security’ were neither vampires nor collecting Social Security, but were real people whose deaths hadn’t been recorded. This was presumably a follow-up to a 2015 story where identity fraud was involved — but again, the government wasn’t losing money, because it wasn’t paying money out to dead people.

The excess population at younger years isn’t explained by this report, but again, the next step is to see what is already known by the people who spend their whole careers working with the data, rather than to decide the explanation is the first thing that comes to mind.