How close is the nearest road in New Zealand?

Gareth Robins has answered this question with a very beautiful visualization generated with a surprisingly compact piece of R code.

Check out the full size image and the coded here.

Gareth Robins has answered this question with a very beautiful visualization generated with a surprisingly compact piece of R code.

Check out the full size image and the coded here.

Today, Wiki New Zealand came to our department to talk about their work. I mentioned them in late 2012 when they first went live, but they’ve developed a lot since then.

The aim of Wiki New Zealand is to have ALL THE DATAS about New Zealand in graphical form, so that people who aren’t necessarily happy with spreadsheets and SQL queries can browse the information. Their front page at the moment has data on cannabis use, greenhouse gas emissions, wine grape and olive plantings, autism, and smoking.

One of the standard science facts that comes in in polls about general scientific ignorance is that the continents move. More than 80% of people in the US know this, but within living memory it went from loony to controversial to accepted to boring enough for school curriculum.

People noticed the similarity of the African and American coastlines as soon as there were maps of both continents, but the idea of millions of square kilometers of land cruising around the earth seemed rather less plausible than a massive coincidence. This, from NOAA is a modern version of one of the most compelling pieces of evidence. The ocean floor is younger along the mid-Atlantic ridge (and similar lines), and gets older, symmetrically, as you move away from the ridge

[the sea turtle migration/continental drift story, though? That’s a myth]

From Malaysian newspaper The Star, via Twitter, an infographic that gets the wrong details right

The designer went to substantial effort to make the area of each figure proportional to the number displayed (it says something about modern statistical computing that the my quickest way to check this was read the image file in R, use cluster analysis to find the figures, then tabulate).

However, it’s not remotely true that typical Malaysians weigh nearly four times as much as typical Cambodians. The number is the proportion above a certain BMI threshold, and that changes quite fast as mean weight increases. Using 1971 US figures for the variability of BMI, you’d get this sort of range of proportion overweight with a 23% range in mean weight between the highest and lowest countries.

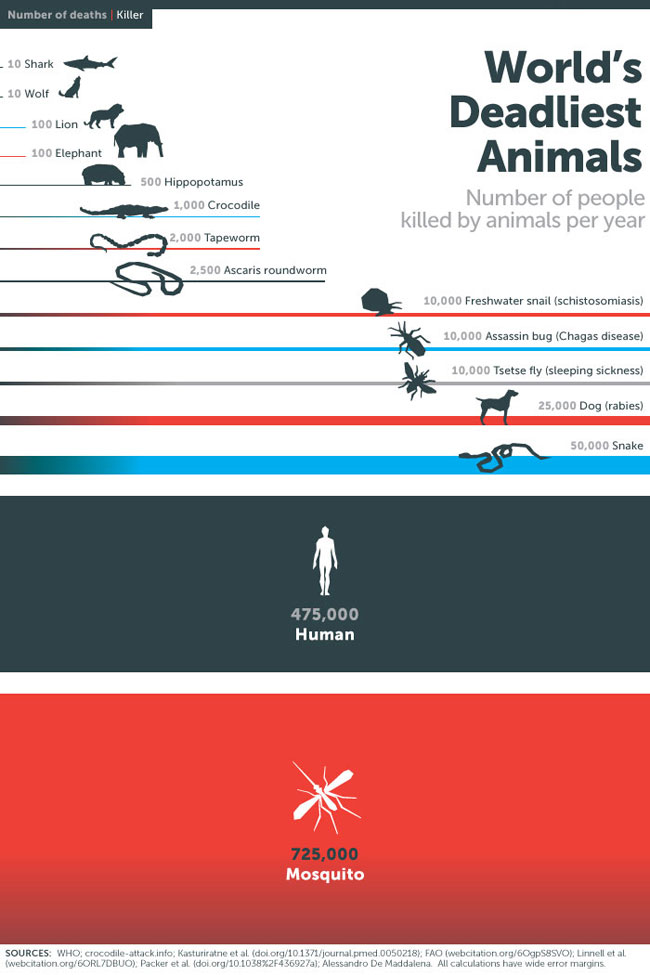

An infographic tweeted by Bill Gates recently on the world’s deadliest animals

He’s trying to make the point that malaria is a really big deal, killing more people than human violence, which is true, and which is the impression from the infographic, so it’s not misleading in that sense.

However, mosquitos don’t rend people limb from limb. The mosquito deaths are due to mosquitos infecting people with malaria parasites. The human deaths, however, are just directly due to violence. If he’d included deaths due to human-human transmission of infection (influenza, tuberculosis, HIV, …), humans would easily be at the top of the list again.

Edward Tufte coined the phrase ‘the Pravda school of ordinal graphics’, reminding us that numbers have a magnitude as well as a direction. Nowadays, he might have named the problem for Fox News.

I wrote about this one last month

Today’s (historical) effort, via Ben Atkinson

Interestingly, although they could use exactly the same barchart every time, they don’t. The Obamacare chart representing the data ratio 7066/6000 = 1.17 by a height ratio of 2.8; the tax cut chart represents the very similar data ratio 36.9/35 = 1.13 by a height ratio of 5.

“Waste, Fraud, and Abuse” is a common slogan for cutting government spending. Here, the fraud and abuse is obvious in the bar charts, but I hadn’t realised the extent of wasted effort that must go into redrawing it each time.

To help with interpreting trends in unemployment, the New York Times has two animated bar charts showing the impact of sampling uncertainty. Here’s a snapshot of one of them (click for the real thing)

There’s a lot of uncertainty in ‘job growth’ figures from a single month, and a lot more uncertainty in month to month changes in estimates of job growth.

The graph below is from Kevin Drum at Mother Jones, and is supposed to show US income inequality among college graduates (giving the mean and 10th and 90th percentiles) and between college graduates and people with only a high school education (the zero line). The graph is originally from a report by the Center for American Progress (page 7). Look at the labelling of the y-axis.

As Chad Orzel points out, there is no way these numbers can be right. The blue lines for both men and women cross 100. That should mean the logarithm of the ratio of 90th percentile college-graduate income to high-school graduate income is 100; the top 10% of college graduates would have to earn at least 25 million trillion trillion trillion times more than the average for people with only a high-school education.

Even in the US, income inequality isn’t that bad.

From The Times, via Alberto Cairo and junkcharts, an example of how to make an unreadable infographic from two bar charts. Both are at weird angles, one is 3-d and one is half-missing.

[Yes, the cargo containers on the boats are colour-coded by the national flags. Isn’t that sweet?]

There’s a good chance you’ve seen this graph and formed an opinion about it already

There certainly hasn’t been any shortage of comment about it, blaming the Florida Department of Law Enforcement for trying to reverse the apparent impact of the law change.

Andy Kirk, at Visualizing Data, has a couple of posts about the chart that you should read. It turns out that the designer of the chart wasn’t the Florida government, it was the C. Chan whose name appears at the bottom left. She designed the chart to try to show the big increase after 2005. She just likes having the y-axis increase downwards for bad things, inspired by this example

It’s interesting to look at why it’s obvious that the red area is the data in this graph, but not obvious in the first graph. Part of it is the title reference to blood, and the fact that the bars can be seen as dripping. Another important clue is that the labels and additional graphs are on the white part of the graph, making it look like background; in the Florida graph the label is on the red section. Finally, the Iraq graph is not tied down at the bottom; the Florida graph has the x-axis at the bottom. The Florida graph is like those faces/goblet ambiguous pictures; for many people it doesn’t have strong enough visual cues for foreground and background to overcome the basic expectation that up is up. A previous example of thoughtful design conflicting with prior expectations about the zero-line for the y-axis was ‘attack of the 14ft cat‘ from last year

I played around with these ideas, and came up with this revision, using a shadow and moving the x-axis to the top (I tried moving the label to the white section, but it didn’t seem to help)

I think it’s a bit easier to see that the red is the foreground here, but it still isn’t really compelling that the red is the data.