PhD gender gap

From Scientific American and Periscopic, an interactive display of international gender differences in PhDs awarded in various fields.

From Scientific American and Periscopic, an interactive display of international gender differences in PhDs awarded in various fields.

The Herald has an interactive election-results map, which will show results for each polling place as they come in, together with demographic information about each electorate. At the moment it’s showing the 2011 election data, and the displays are still being refined — but the Herald has started promoting it, so I figure it’s safe for me to link as well.

Mashblock is also developing an election site. At the moment they have enrolment data by age. Half the people under 35 in Auckland Central seem to be unenrolled,which is a bit scary. Presumably some of them are students enrolled at home, and some haven’t been in NZ long enough to enrol, but still.

Some non-citizens probably don’t know that they are eligible — I almost missed out last time. So, if you know someone who is a permanent resident and has lived in New Zealand for a year, you might just ask if they know about the eligibility rules. Tomorrow is the last day.

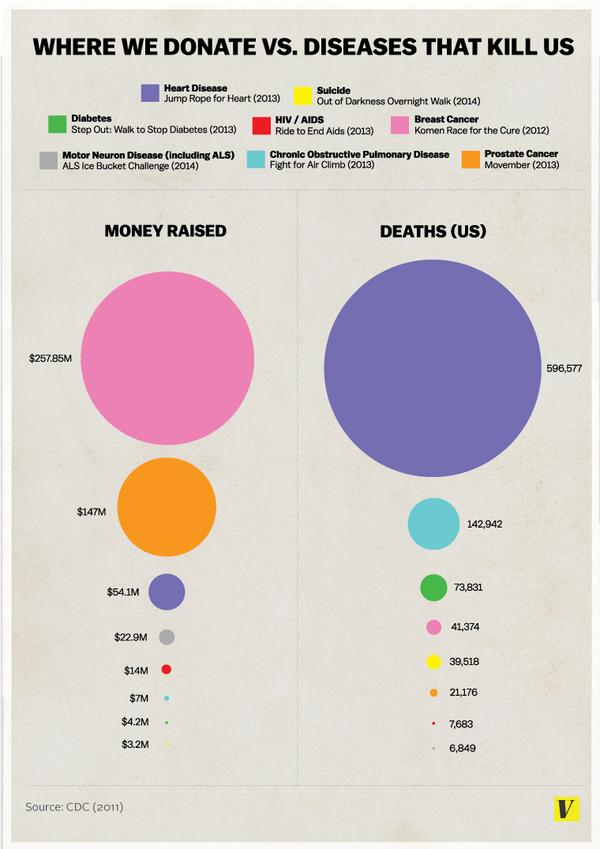

You have probably seen the graphic from vox.com

There are several things wrong with it. From a graphics point of view it doesn’t make any of the relevant comparisons easy. The diameter of the circle is proportional to the deaths or money, exaggerating the differences. And the donation data are basically wrong — the original story tries to make it clear that these are particular events, not all donations for a disease, but it’s the graph that is quoted.

For example, the graph lists $54 million for heart disease, based on the ‘Jump Rope for Heart’ fundraiser. According to Forbes magazine’s list of top charities, the American Heart Association actually received $511 million in private donations in the year to June 2012, almost ten times as much. Almost as much again came in grants for heart disease research from the National Institutes of Health.

There’s another graph I’ve seen on Twitter, which shows what could have been done to make the comparisons clearer:

It’s limited, because it only shows government funding, not private charity, but it shows the relationship between funding and the aggregate loss of health and life for a wide range of diseases.

There are a few outliers, and some of them are for interesting reasons. Tuberculosis is not currently a major health problem in the US, but it is in other countries, and there’s a real risk that it could spread to the US. AIDS is highly funded partly because of successful lobbying, partly because it — like TB — is a foreign-aid issue, and partly because it has been scientifically rewarding and interesting. COPD and lung cancer are going to become much less common in the future, as the victims of the century-long smoking epidemic die off.

Depression and injuries, though?

Update: here’s how distorted the areas are: the purple number is about 4.2 times the blue number

A recurring issue with trends over time is whether they are ‘age’ trends, ‘period’ trends, or ‘cohort’ trends. That is, when we complain about ‘kids these days’, is it ‘kids’ or ‘these days’ that’s the problem? Mark Liberman at Language Log has a nice example using analyses by Joe Fruehwald.

If you look at the frequency of “um” in speech (in this case in Philadelphia), it decreases with age at any given year

On the other hand, it increases over time for people in a given age cohort (for example, the line that stretches right across the graph is for people born in the 1950s)

It’s not that people say “um” less as they get older, it’s that people born a long time ago say “um” less than people born recently.

Infographic edition

1. Thomson Reuters illustrated the importance of fine detail in graphic in one of their ads. It looks like a Venn diagram. Oops.

Removing the transparent overlap and changing the colours makes it less Venn-ish

2. Kevin Schaul in the Washington Post came up with this neat graphical summary of state data

Because the basic outline of the US is so familiar (especially to people who live there), the huge spatial distortions aren’t actually all that disturbing. Mark Monmonier, a geographer, seems to have been the first person to move in this direction (eg). I suggested to Kevin, on Twitter, that this technique would also allow Alaska to be moved from the tropical Pacific to its proper home in the north, and he agreed.

3. That’ll wake you up

Jawbone, who make products that tell you if you are awake and walking around, looked at the impact of this week’s Napa earthquake. The data resolution isn’t quite fine enough to see the time taken for the ground waves to propagate — compare XKCD on the Twitter event horizon

From XKCD. Both the data and the display technique are worth looking at

Presumably you could do something similar with New Zealand, which is roughly the same shape.

From floatingsheep.org

Ultimately, despite the centrality of social media to the protests and our ability to come together and reflect on the social problems at the root of Michael Brown’s shooting, these maps, and the kind of data used to create them, can’t tell us much about the deep-seated issues that have led to the killing of yet another unarmed young black man in our country. And they almost certainly won’t change anyone’s mind about racism in America. They can, instead, help us to better understand how these events have been reflected on social media, and how even purportedly global news stories are always connected to particular places in specific ways.

One frame of a video showing NZ party representation in Parliament over time,

made by Stella Blake-Kelly for TheWireless. Watch (and read) the whole thing.

Via Alberto Cairo on Twitter, a picture from an introductory statistics text being sold at the big statistics conference in Boston this week

This map, from Reddit, shows the most common name in each county of England and Wales in 1881, based on the 1881 census.

Matthew Yglesias at Vox.com says “what’s remarkable is how nearly perfectly the Smith/Jones divide lines up with the political boundary between England and Wales”. I think it’s remarkable that he think’s it’s remarkable — I think of ‘Jones’ as the stereotypical Welsh name — but obviously associations are different in the US. It is worth pointing out that the line-up isn’t as good as you might think if you weren’t careful: three of the light-green counties are actually in England, not in Wales.

Yglesias also says that the names “seem to show pretty distinctively what part of the British Isles your male line hails from.” That’s an example of how maps are systematically misleading — the conclusion may be true, but the map doesn’t support it as strongly as it seems to. The map shows the most common name in each county, and most of the counties where Jones is the most common name are Welsh. However, that doesn’t mean most people called Jones were in Wales. In fact, based on search counts from UKCensusOnline.com, Lancashire had more Joneses than any Welsh county, and London had more than all but two Welsh counties. Overall, only 51% of Joneses were in Wales, going up to 60% if you include the three English counties coloured light green on the map.

In this particular case, many non-Welsh Joneses probably did have Welsh ancestors who had left Wales well before 1881, but not all of them — according to Wikipedia, the name came from Norman French and the first recorded use was in England.