Evil within?

The headline: Sex and violence ‘normal’ for boys who kill women in video games: study. That’s a pretty strong statement, and the claim quotes imply we’re going to find out who made it. We don’t.

The (much-weaker) take-home message:

The researchers’ conclusion: Sexist games may shrink boys’ empathy for female victims.

The detail:

The researchers then showed each student a photo of a bruised girl who, they said, had been beaten by a boy. They asked: On a scale of one to seven, how much sympathy do you have for her?

The male students who had just played Grand Theft Auto – and also related to the protagonist – felt least bad for her. with an empathy mean score of 3. Those who had played the other games, however, exhibited more compassion. And female students who played the same rounds of Grand Theft Auto had a mean empathy score of 5.3.

The important part is between the dashes: male students who related more to the protagonist in Grand Theft Auto had less empathy for a female victim. There’s no evidence given that this was a result of playing Grand Theft Auto, since the researchers (obviously) didn’t ask about how people who didn’t play that game related to its protagonist.

What I wanted to know was how the empathy scores compared by which game the students played, separately by gender. The research paper didn’t report the analysis I wanted, but thanks to the wonders of Open Science, their data are available.

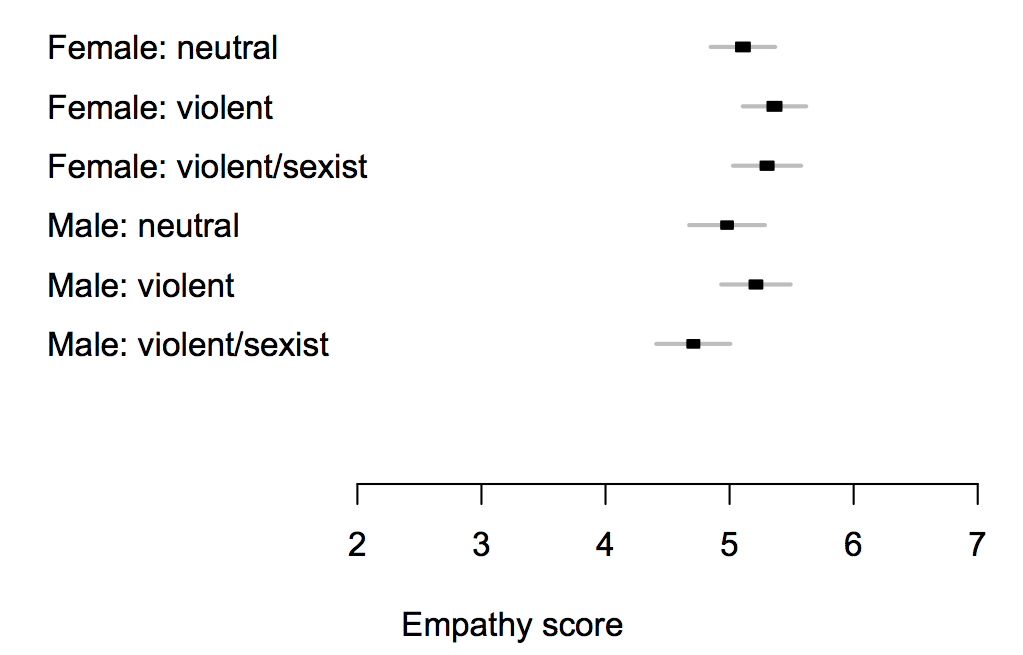

If you just compare which game the students were assigned to (and their gender), here are the means; the intervals are set up so there’s a statistically significant difference between two groups when their intervals don’t overlap.

The difference between different games is too small to pick out reliably at this sample size, but is less than half a point on the scale — and while the ‘violent/sexist’ games might reduce empathy, there’s just as much evidence (ie, not very much) that the ‘violent’ ones increase it.

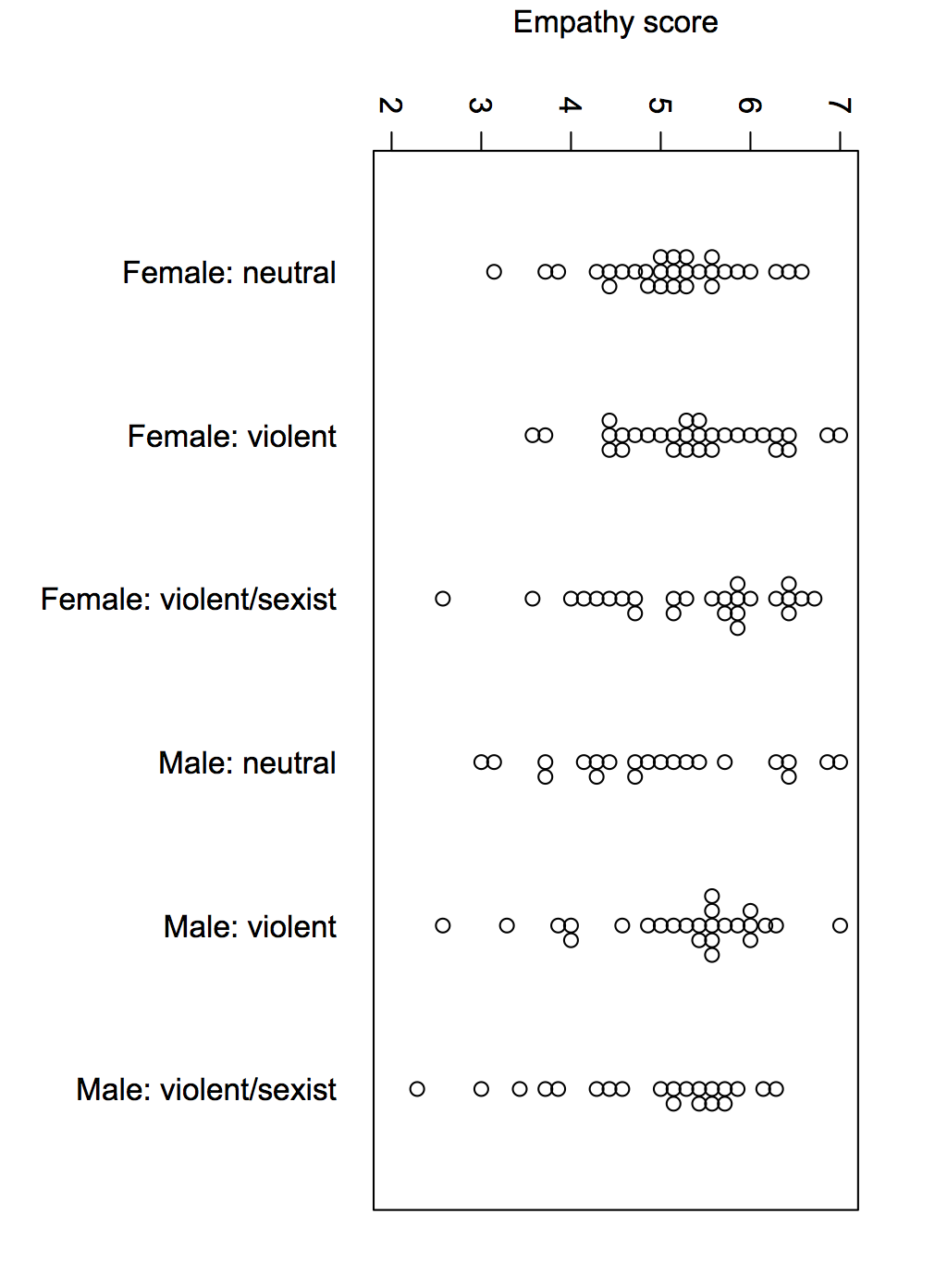

Here’s the complete data, because means can be misleading

The data are consistent with a small overall impact of the game, or no real impact. They’re consistent with a moderately large impact on a subset of susceptible men, but equally consistent with some men just being horrible people.

If this is an issue you’ve considered in the past, this study shouldn’t be enough to alter your views much, and if it isn’t an issue you’ve considered in the past, it wouldn’t be the place to start.