I wrote before about estimating the proportion of spam bots among the apparent people on Twitter. The way Twitter does it seems ok. According to some people in the internet who seem to know about Delaware mergers and acquisitions law it doesn’t even matter if the way Twitter does it is ok, as long as it roughly matches what they have claimed they do. But it’s still interesting from a statistics point of view to ask whether it could be done better given the existence of predictive models (“AI”, if you must). It’s also connected to my research.

Imagine we have a magic black box that spits out “Bot” or “Not” for each user. We don’t know how it works (it’s magic) and we don’t know how much to trust it (it’s magic). We feed in the account details of 217 million monetisable daily active users and it chugs and whirrs for a while before saying “You have 15696969 bots.”

We’re not going to just tell investors “A magic box says we have 15696969 bots among our daily active users“, but it’s still useful information. We also have reviewed a genuine random sample of 1000 accounts by hand, over a couple of weeks, and we get 54 bots. We don’t want to just ignore the magic box and say “we have 5.4% bots” What should our estimate be, combining the two? It obviously depends on how accurate the magic box is! We can get some idea by looking at what the magic box says for the 1000 accounts reviewed by hand.

Maybe the magic box says 74 of the 1000 accounts are bots: 50 of the ones that really are, and 24 others. That means it’s fairly accurate, but it overcounts by about 40%. Over all of Twitter, you probably don’t have 15696969 bots; maybe you have more like 11,420,000 bots. If we want the best estimate that doesn’t require trusting the magic box and only requires trusting the random sampling, we can divide up Twitter into accounts the box says are bots and ones that it says aren’t bots, estimate the true proportion in each group, and combine. In this example, we’d get 5.3% with a 95% confidence interval of (4.4%, 6.2%). If we didn’t have the magic box at all, we’d get an estimate of 5.4% with a confidence interval of (4.0%, 6.8%). The magic box has improved the precision of the estimate. With this technique, the magic box can only be helpful. If it’s accurate, we’ll get a big improvement in precision. If it’s not accurate, we’ll get little or no improvement in precision, but we still won’t introduce any bias.

The techique is called post-stratification, and it’s the simplest form of a very general approach to using information about a whole population to improve an estimate from a random sample. Improving estimates of proportions or counts with post-stratification is a very old idea (well, very old by the standards of statistics). More recent research in this area includes ways to improve estimation of more complicated statistical estimates, such as regression models. We also look at ways to use the magic box to pick a better random sample — in this example, instead of picking 1000 users at random we might pick a random sample of 500 accounts that the magic box says are bots and 500 accounts that it says are people. Or maybe it’s more reliable on old accounts than new ones, and we want to take random samples from more new accounts and fewer old accounts.

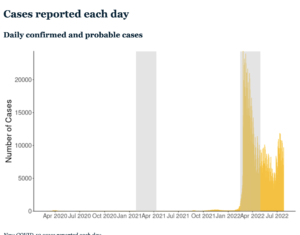

In practical applications the real limit on this idea is the difficulty of doing random sampling. For Twitter, that’s easy. It’s feasible when you’re choosing which medical records from a database to check by hand, or which frozen blood samples to analyse, or which Covid PCR swabs to send for genome sequencing. If you’re sampling people, though, the big challenge is non-response. Many people just won’t fill in your forms or talk to you on the phone or whatever. Post-stratification can be part of the solution there, too, but the problem is a lot messier.

Recent comments on Thomas Lumley’s posts