Maths

Q: Did you see that learning maths can affect your brain?

A: Well, yes. There wouldn’t be much point otherwise

Q: No, biochemically affect it

A: Yes, that’s how learning works

Q: But the researchers “can actually guess with a very good accuracy whether someone is continuing to study maths or not just based on the concentration of this chemical in their brain.”

A: How good is “very good”?

Q: I thought I was the one who asked those questions.

A:

Q: How good is “very good”?

A: The research paper doesn’t say

Q: Can you get their data?

A: <downloading and analysis noises>

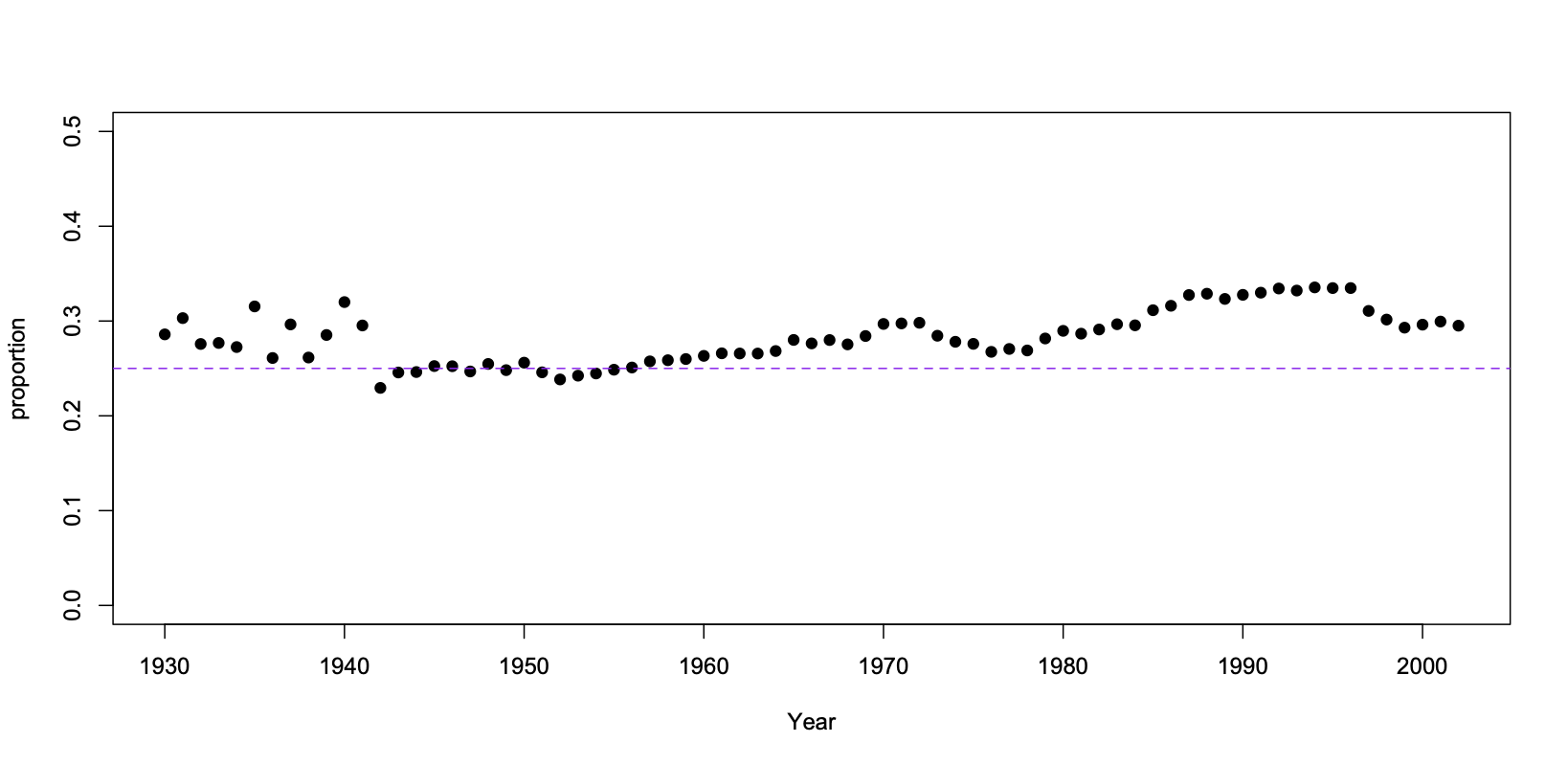

A: Ok, so in their data you can get about 66% accuracy, 55 correct out of 83, using this brain chemical

Q: And just by guessing?

A: 56% (46 out of 83)

Q: Are these changes in the brain good? I mean, apart from learning maths being good for learning maths?

A: That seems to be assumed, but they don’t explain why

Q: And what about subjects other than maths?

A: The Herald piece says the differences they saw with maths don’t happen with any other subject, but the research paper doesn’t say they did the comparisons — in fact, it more or less denies that they did, because it talks about how many comparisons they did just in terms of two brain regions and two chemicals, not in terms of other subjects studied.

Q: But in any case, learning some other subject might still cause different changes in the brain

A: I think we can guarantee that it does, yes

Recent comments on Thomas Lumley’s posts