How many omicrons (recap)

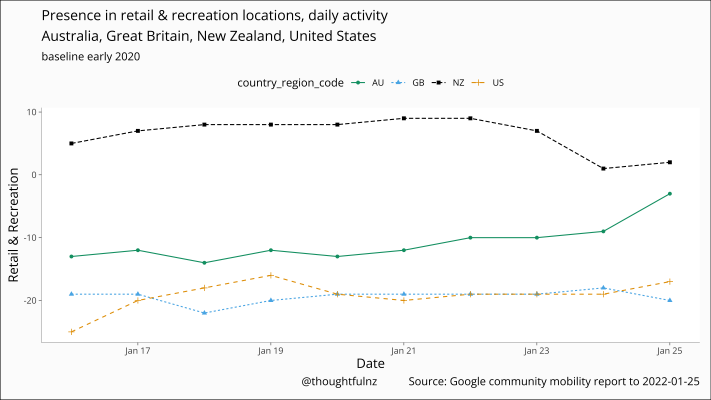

Now we’re at Waitangi weekend we can confirm that New Zealand modellers and epidemiologists, none of whom expected 50,000 cases per day at this point, were correct. Unfortunately, the Herald has

Questioned on earlier figures that up to 50,000 new cases would be emerging by Waitangi Day – and 80,000 a day a few weeks later – Hipkins described the calculations as useful, saying it was better to have some modelling than none.

Further down, the Herald piece admits that these figures didn’t come from the New Zealand modellers that the Minister is paying and being advised by, but from IHME in Seattle. It’s worse than that, though. The only place I saw tens of thousands of cases as a description of the modelling by the IHME in Seattle was in a Herald headline.

All the other reporting of it that I saw at least said “infections”, even if they weren’t clear enough that this wasn’t remotely the same as cases.

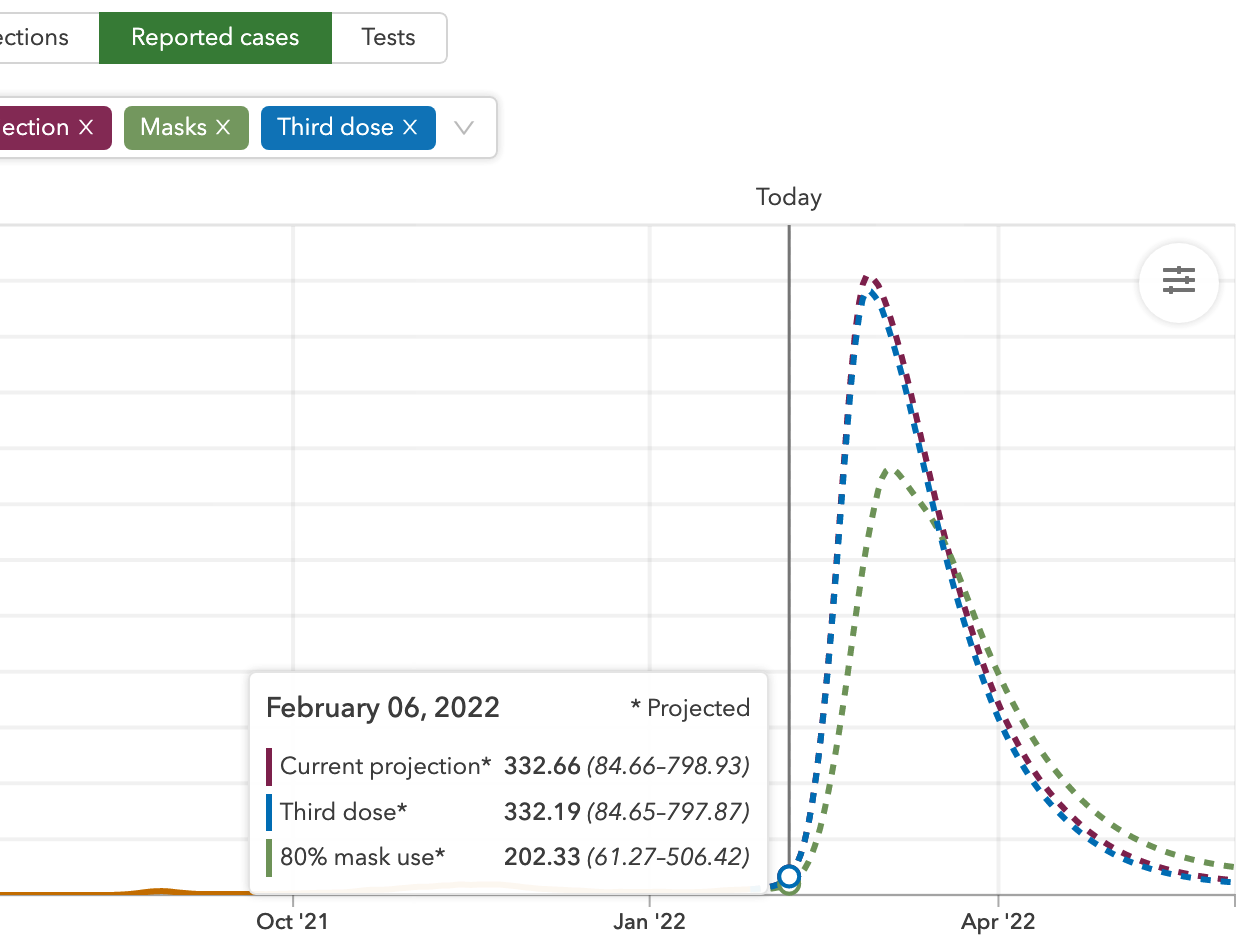

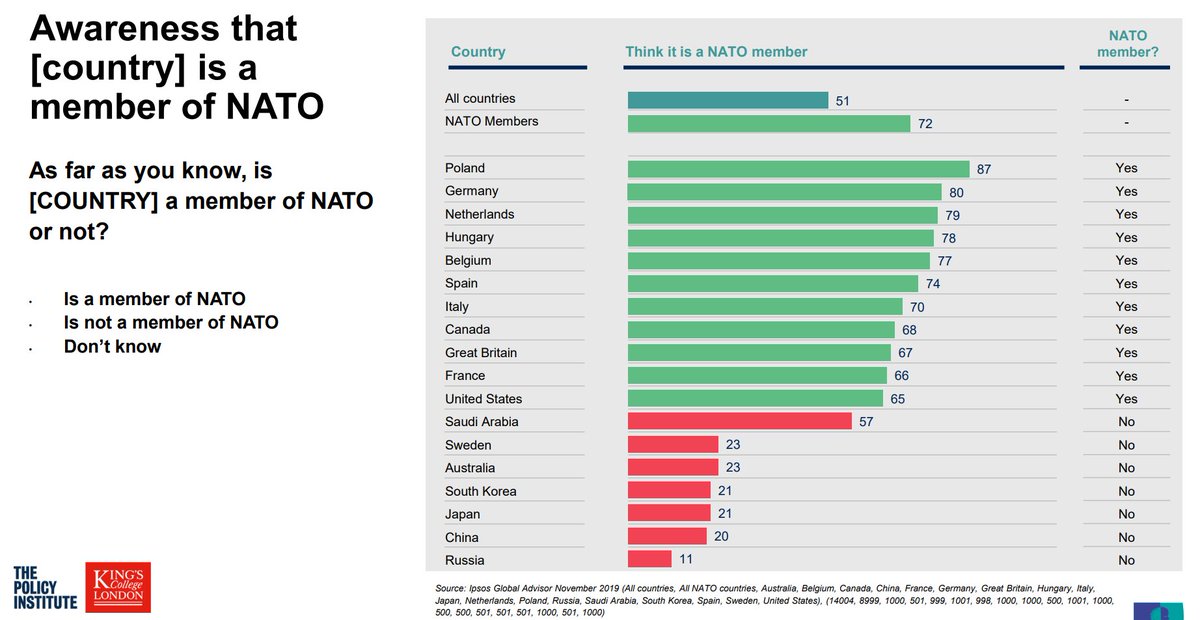

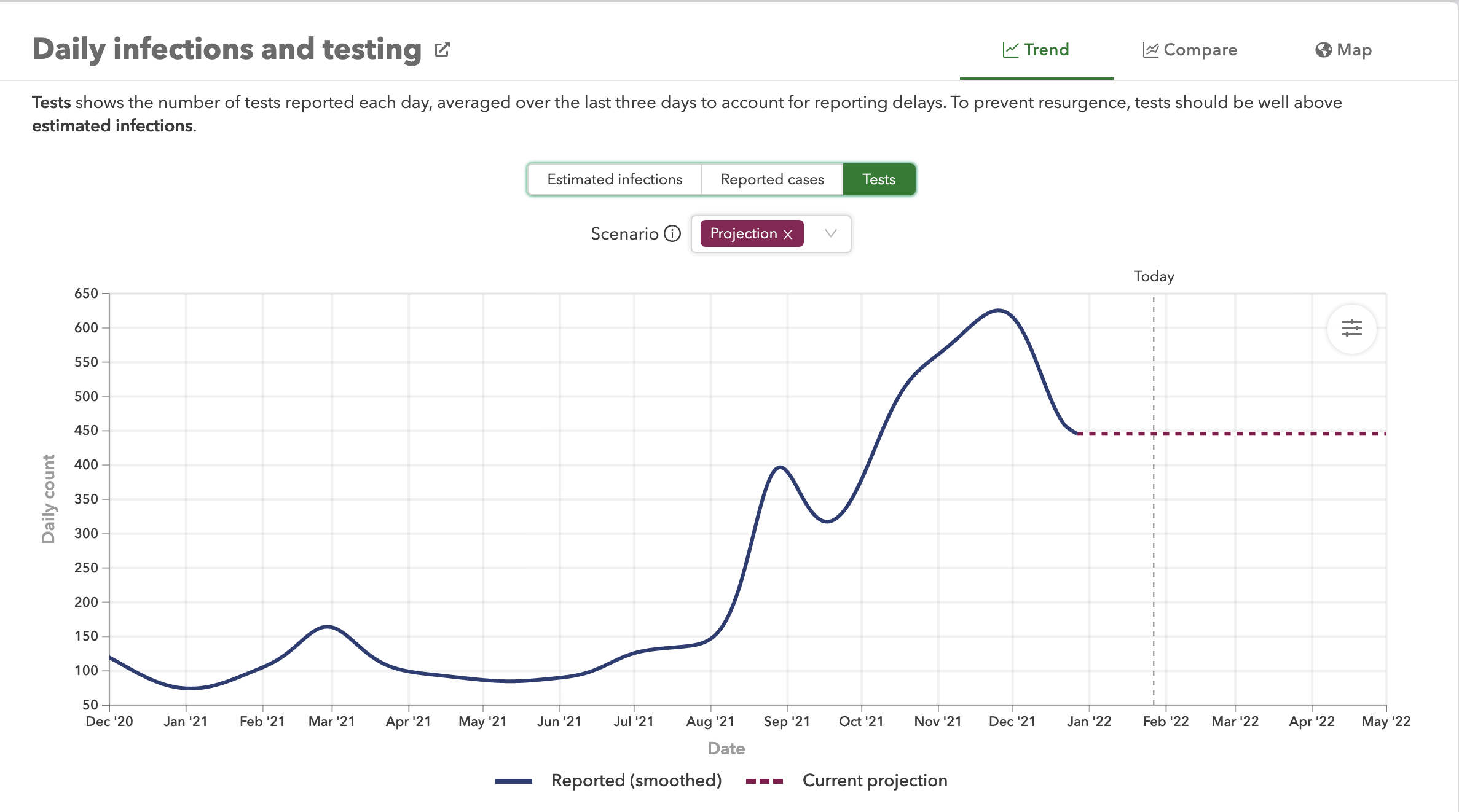

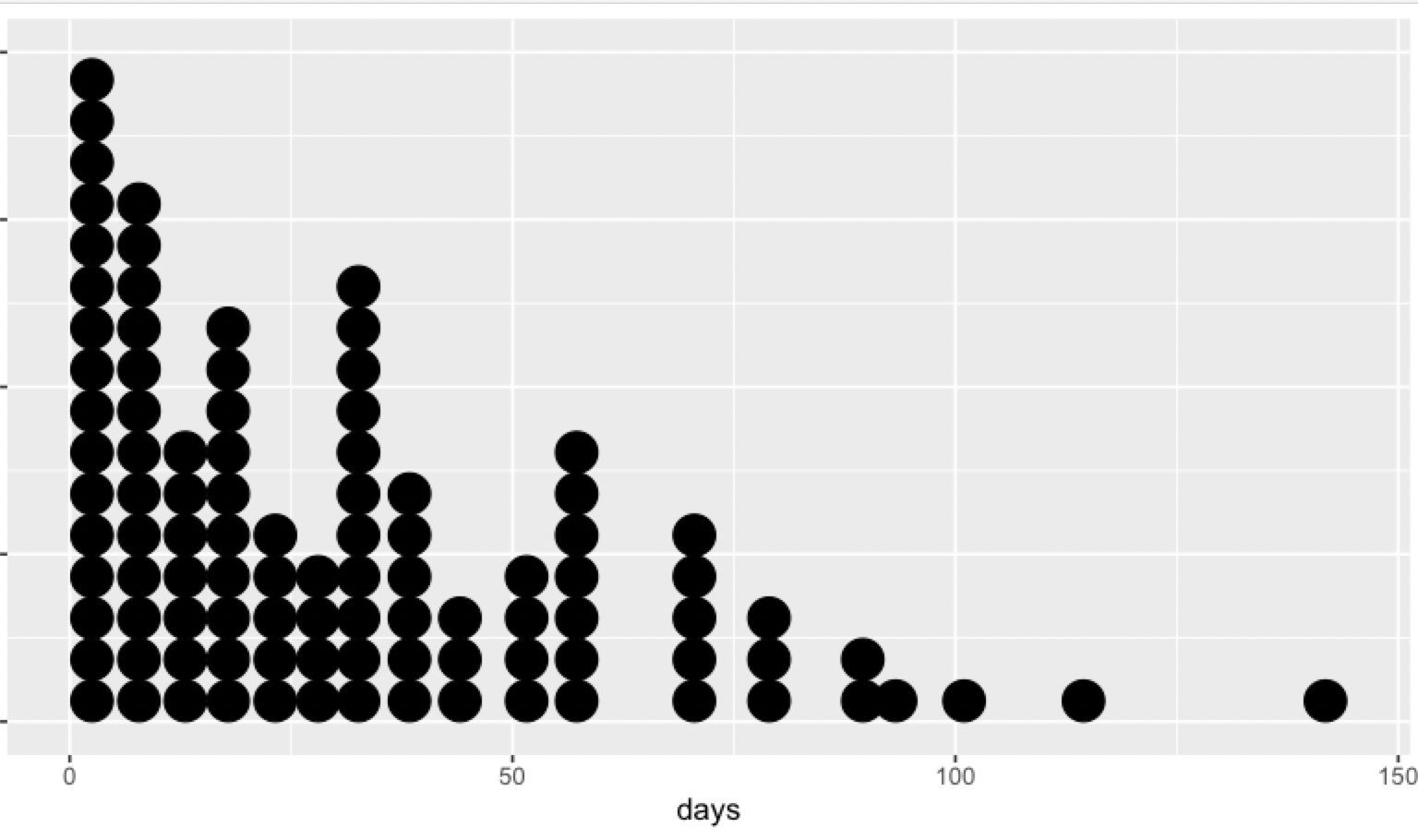

As you can see, the IHME model prediction for reported cases today, Sunday 6 February, was actually 332 (or 202 with good mask use), even though the projection for infections by tomorrow was nearly 50,000.

The uncertainty interval for that projected 332 went from 85 to nearly 800, so the actual figure was well inside the predicted range.

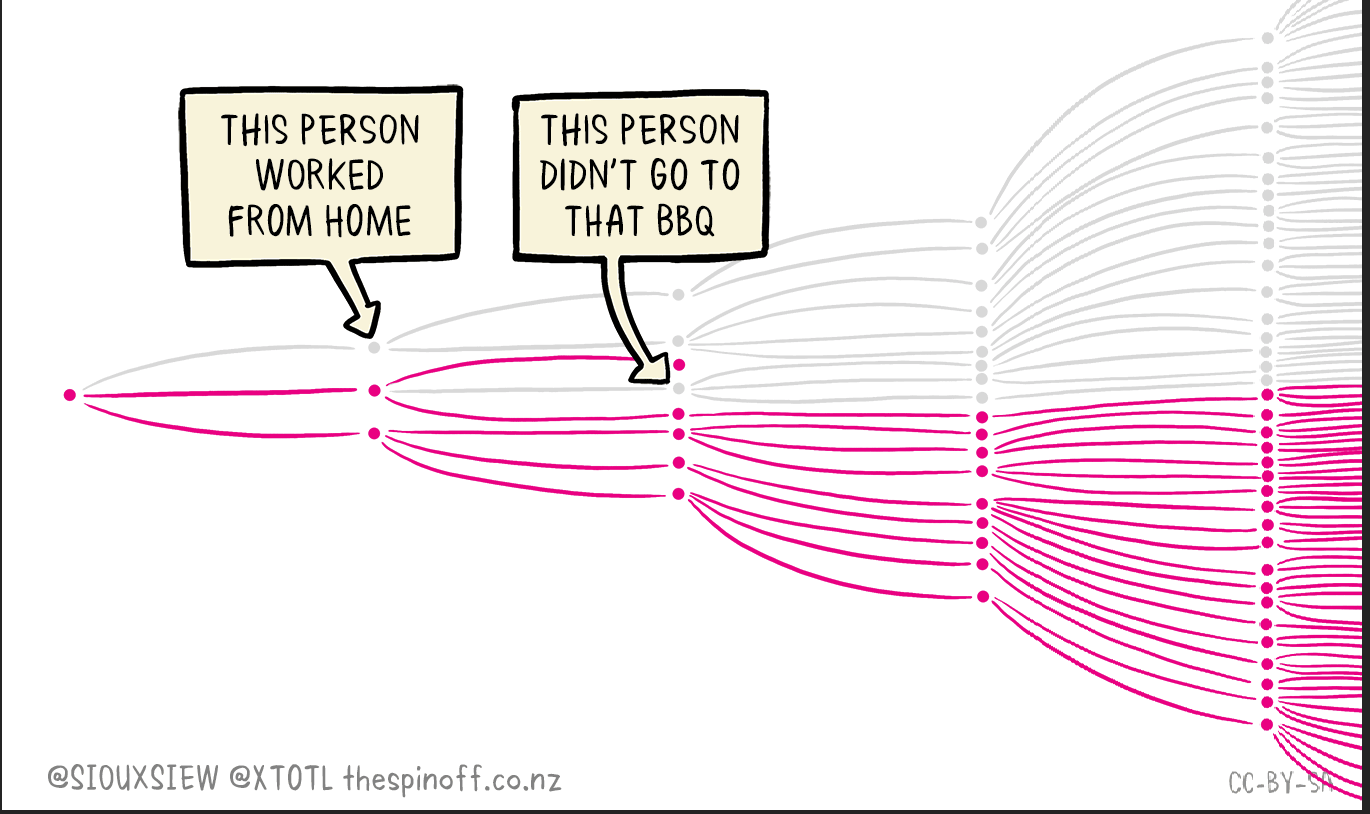

You might think that this sort of accuracy still isn’t very good. Projecting the timing of the epidemic is hard — think of the exponential-spread cartoon from Toby Morris and Siouxsie Wiles

Especially early on in an outbreak, individual choices and luck can make a big difference to how fast the outbreak spreads. Eventually it will be overall patterns of vaccination and masking and distancing and isolation that matter for the overall outbreak size. The models will be more accurate as the outbreak gets bigger and less random, and they will likely be more accurate about total outbreak size than about timing.

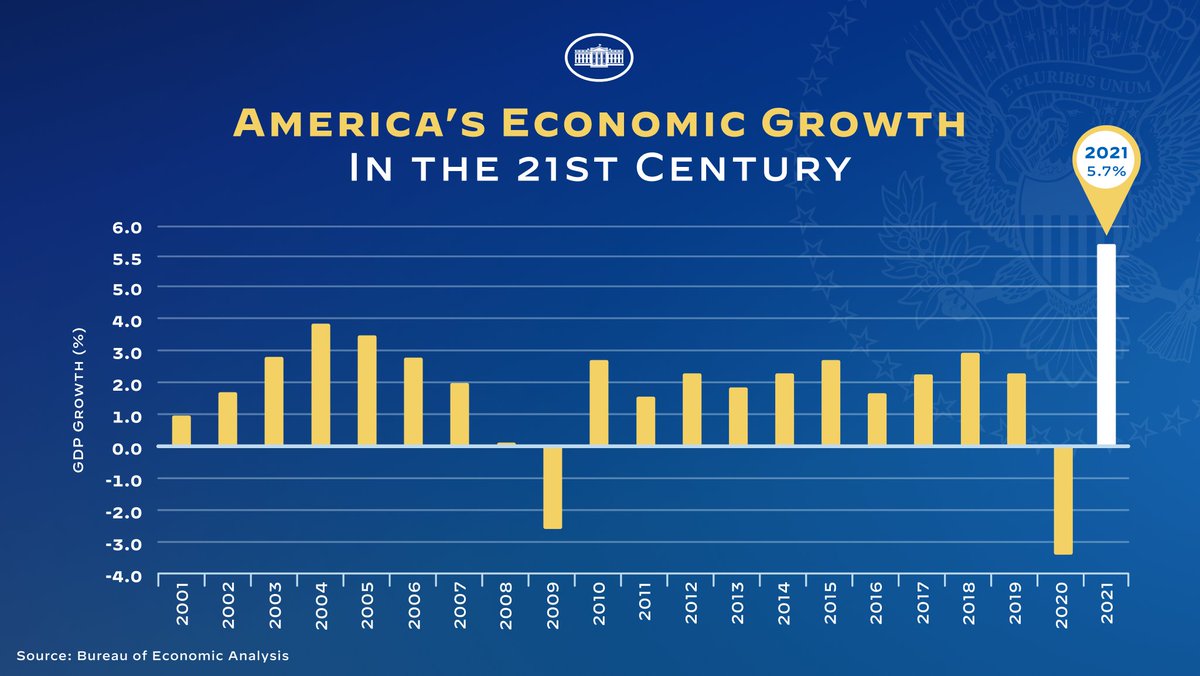

I’m not a fan of the IHME models — they have notoriously been overly optimistic in the medium to long term in the US — but Michael Baker and the Otago group think they’re reasonable, and you should arguably listen to them rather than me on this topic. We’ll find out soon. Whatever you think of them in general, though, the modellers certainly didn’t predict 50,000 cases by today, and shouldn’t be criticised for failing to predict something that didn’t happen.

Recent comments on Thomas Lumley’s posts