The Herald and the Spinoff both commented on the Covid testing results yesterday. The Spinoff had a quick paragraph

While the tally of new cases is down, the test positivity rate is up. Yesterday’s report saw 21,471 tests and 243 positive cases – a one in 88 result; today it was 16,873 tests and 208 new cases: a one in 81 result.

and the Herald had a detailed story with quotes from experts

Experts believe Covid fatigue and a perception that Omicron is less of a threat than Delta are to blame for low testing numbers at the start of the community outbreak.

There were 100,000 fewer tests administered in the week following Omicron community transmission than the week following Delta transmission, Ministry of Health data shows.

They’re both right, but the Ministry of Health is not giving out the most helpful numbers or comparisons to understand how much it’s really a problem.

There are three basic reasons for testing: regular surveillance for people in certain high-risk jobs, testing of contacts, and testing of people with symptoms. The number of surveillance tests is pretty much uninformative — it’s just a policy choice — but the proportion of positive tests is a strong signal. The number of tests done for (not yet symptomatic) close contacts tells us about the effectiveness of contact tracing and about the number of cases in recent days (which we knew), but it doesn’t tell us much else, and the positivity rate will mostly depend on who we define as close contacts rather than on anything about the epidemic. The number of tests prompted by symptoms actually is an indicator of willingness to test, and the test positivity rate is an indicator of Covid prevalence, but only up to a point.

There’s another external factor confusing the interpretation of changes in symptomatic testing: the seasonal changes in the rate of other illnesses. When Delta appeared, testing was higher than when Omicron appeared. That could be partly because people (wrongly) thought Omicron didn’t matter, or (wrongly) thought it couldn’t be controlled, or (perhaps correctly) worried that their employers would be less supportive of being absent, or thought the public health system didn’t care as much or something. It will also be partly because fewer people have colds in December than in August.

As a result of much collective mahi and good luck, most of the people getting tested because of symptoms actually have some other viral upper-respiratory illness, not Covid. At times of year when there is more not-actually-Covid illness, testing rates should be higher. August is winter and kids had been at school and daycare; it’s the peak season for not-actually-Covid. December, with school out and after a long lockdown to suppress various other viruses, is low season for not-actually-Covid. Fewer tests in December is not a surprise.

Not only will more colds mean more testing, they will also mean a lower test positivity rate — at the extreme if there were no other illnesses, everyone with symptoms would have Covid. The two key testing statistics, counts and positivity rate, are hard to interpret in comparisons between now and August.

It would help some if the Ministry of Health reported test numbers and results by reason for testing: contacts, symptoms, regular surveillance. It would help to compare symptomatic testing rates with independent estimates of the background rate of symptoms (eg from Flutracker). But it’s always going to be hard to interpret differences over long periods of time — differences over a few weeks are easier to interpret, preferably averaged over more than one day of reporting to reduce random noise.

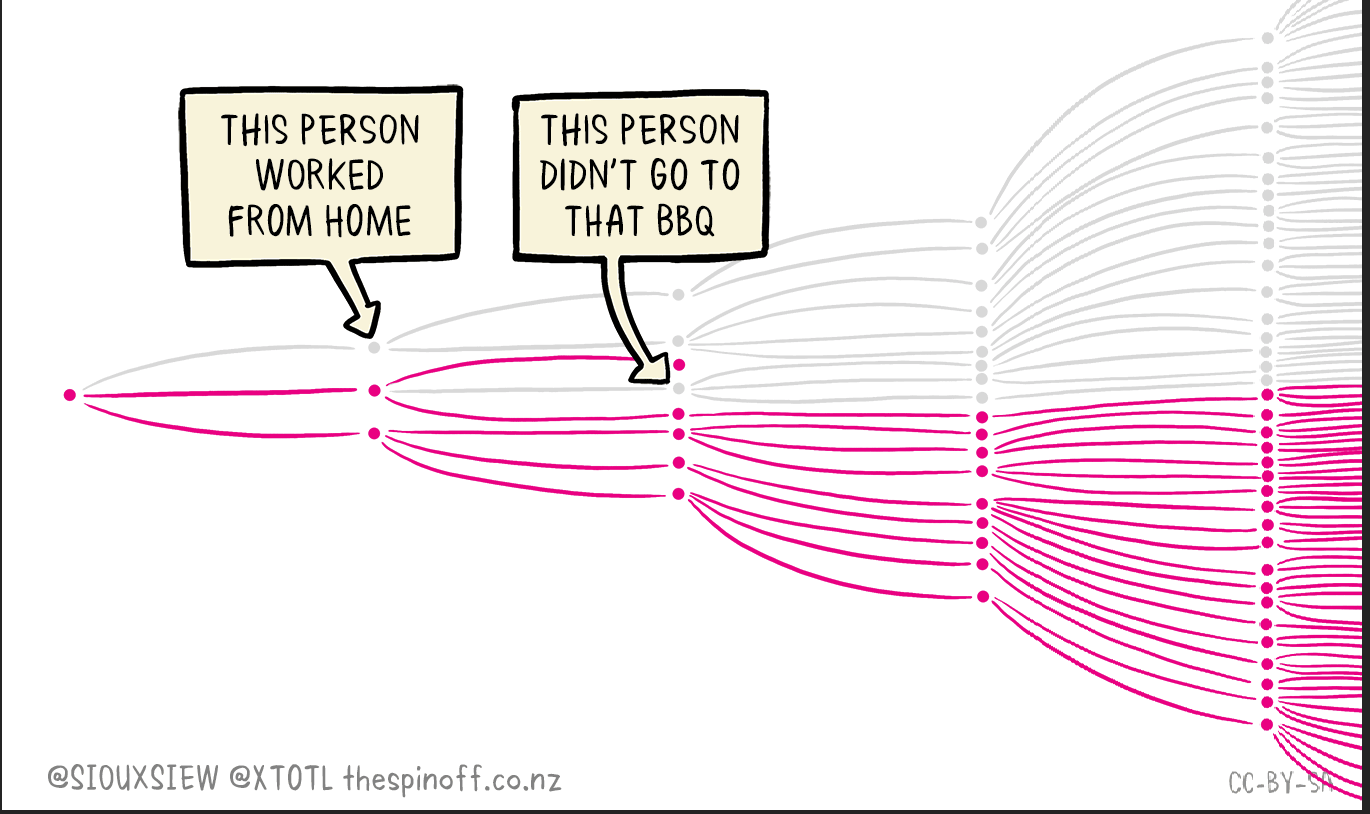

None of this is to disagree with the call for people with symptoms to get tested. We know not everyone with symptoms is tested; it’s probably been a minority throughout the pandemic. Getting the rate up would help flatten the wave of Omicron along with masks and vaccines and everything else.