New Zealand and international media are reporting an new analysis of the gender pay gap among NZ academics. At one level this isn’t anything very surprising: there’s a gender pay gap, of the same percentage order of magnitude as in NZ as a whole (larger in Medicine, smaller in Arts).

As I’ve pointed out before, we know this is caused by gender, it’s not just some sort of correlation caused by confounding factors, since there aren’t any. What’s interesting is how it is that women come to be paid less. You could imagine a range of direct mechanisms:

- slower promotion

- lower pay at the same grade

- less likely to be head of department/school

- more likely to be at institutions where pay is lower

- more likely to be in fields where pay is lower

And you could imagine possible factors leading into these

- lower research ability

- lower average age, because of past discrimination

- interested in putting more effort into teaching or into service

- pushed into putting more effort into teaching or into service

- interested in putting more effort into childcare

- pushed into putting more effort into childcare

- discrimination in salary assignments

- discrimination in promotion

and so on.

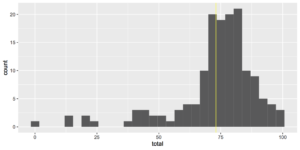

While many people have more or less informed opinions about these mechanisms, it’s often hard to get good data. The research (by Associate Professors Ann Brower and Alex James of the University of Canterbury) takes advantage of the 2018 PBRF evaluations of NZ academics. These evaluations were based on research portfolios selected to show the best research from each person (quality rather than quantity) and were evaluated by panels of NZ and overseas experts in each field.

In this paper, Brower and James got access to PBRF ratings and salary data for NZ academics, and so could look at whether women of similar age with similar PBRF scores had similar pay. As will surely astonish you, they didn’t. In particular, it appears that women are less likely to be promoted to Associate Professor and Professor, with similar PBRF ratings, that men are. Differences in age distribution and research performance explain about half the gender pay gap; the other half remains.

The big limitation of any analysis of this sort is the quality of the performance data. If performance is measured poorly, then even if it really does completely explain the outcomes, it will look as if there’s a unexplained gap. The point of this paper is that PBRF is quite a good measurement of research performance: assessed by scientists in each field, by panels convened with at least some attention to gender representation, using individual, up-to-date information. If you believed that PBRF was pretty random and unreliable, you wouldn’t be impressed by these analyses: if PBRF scores don’t describe research performance well, they can’t explain its effect on pay and promotion well.

There could be bias in the other direction, too. Suppose PBRF were biased in favour of men, and promotions were biased in favour of men in exactly the same way. Adjusting for PBRF would then completely reproduce the bias in promotion, and make it look as if pay was completely fair.

Now, I’m potentially biased, since I was on a PBRF panel in 2013 (and since I got a good PBRF score), but I think PBRF is a fairly good assessment. I think the true residual pay gap could easily be quite a bit smaller or larger than this analysis estimates, but it’s as good as you’re likely to be able to do, and it certainly does not support the view that the pay gap is zero.