Australian Di Cook @visnut was one of several leading women in data science who attended this week’s joint conference of the New Zealand Statistical Association, the International Association o f Statistical Computing (Asian Regional Section) and the Operations Research Society of New Zealand at the University of Auckland, so we couldn’t miss the opportunity to talk with her. A brief bio: Di is a world leader in data visualisation and well-known for her work on interactive graphics. She is Professor of Business Analytics in the Department of Econometrics and Business Statistics at Monash University. She’s a Fellow of the American Statistical Association, elected member of the R Foundation and the Editor of the Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. Her research lies in data science, data visualisation, exploratory data analysis, data mining, high-dimensional methods and statistical computing.

f Statistical Computing (Asian Regional Section) and the Operations Research Society of New Zealand at the University of Auckland, so we couldn’t miss the opportunity to talk with her. A brief bio: Di is a world leader in data visualisation and well-known for her work on interactive graphics. She is Professor of Business Analytics in the Department of Econometrics and Business Statistics at Monash University. She’s a Fellow of the American Statistical Association, elected member of the R Foundation and the Editor of the Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. Her research lies in data science, data visualisation, exploratory data analysis, data mining, high-dimensional methods and statistical computing.

Statschat: When did you first encounter statistics? Di: It was in my undergraduate degree. I studied mathematics with a plan to do math teaching. Statistics was one of the areas of mathematics that I could major in other than pure, or applied, mathematics. There was an extremely good female professor at the University of New England, Eve Bofinger, and I was drawn to some of the methods she was teaching, and that led me into statistics.

What was your career path after that? I taught math at high school for about three months, then I had an offer from the Australian National University to go there as a research assistant, and that seemed a better fit. As a research assistant, I got to learn a lot more things, particularly computing. Computing, I think, is a critical aspect of data science today.

I spent a few years doing that and then realised I’d really like to make art, because some of the research-assistant work I was doing was computer graphics for data online. It fed into my art instincts from teenage years, so I spent some time as an artist before finding a graduate programme in statistics in the US that focused on data visualisation.

What sort of art do you do? I was painting – I haven’t done any for a long, long time, since I finished my PhD; it’s been too busy.

So your creative pursuits have fed into your career. Yeah – seeing that I could do data visualisation as a part of the statistics allowed me to realise that I could do a higher degree in stats; that merged my interests very well.

Where did you do your PhD? At Rutgers University in New Jersey.

You spent 22 years at Iowa State University in the US, and moved to Monash in Australia in 2015. What are your major projects there? I have a lot of projects. One of them is with Tennis Australia; we’ve been looking at tennis serves. So we have Hawk-Eye trajectory data and we visualise the tennis serves and look at how the players are different or similar.

That’s very cool – how’s that for applied statistics. Yeah, it’s fantastic, isn’t it. We’re also looking at face recognition in tennis video, to be able to detect the face through broadcast video, so that we can monitor emotions throughout a match and see how that affects performance.

We’re also looking at pedestrian sensor data, that comes from a city of Melbourne (almost live) feed. One of my PhD students, Earo, has a new type of plot called a calendar plot; you make your data plots into a calendar format so that you can study things relative to holidays, and put it really on a human pattern basis.

Describe a typical day at work at Monash. We have a lot of meetings with students, so I would meet up with two or three students – PhD students or postdocs or research assistants – on projects that we’re working with, and meet up with other faculty. On some days I’m teaching data science classes to around 200 students. We often just go for a coffee with colleagues. We also play ping-pong on the conference table! I’ve got a good group of colleagues who play tennis, so we play tennis together.

It sounds very collegial. You’re a prominent woman in data science, and the field seems to appeal to women as a career path. Do have any thoughts on that? I haven’t really looked at those numbers … but honestly, I think there’s too big of an emphasis on gender differences, and they’re not real when you look at the metrics. It’s just a perception. But one of the things I notice with the women that I work with is that they are interested in solving problems, and having an outcome of their work that makes life better for others. And that’s one thing that data science offers that pure statistics research is a bit removed from.

Do you have a family? I have one son. I moved to Monash after he graduated high school. He went off to college in the US, while I moved halfway across the globe, which he was quite happy about. He visits during the holidays, and last American summer found an internship at Monash University.

When he was small, how did you navigate work and life? It’s really difficult. I can’t imagine how single women do that – you need to have some sort of support mechanism. Day-care is amazing – and however much you spend on day-care, it’s worth it. And also partly because I think young kids early on really get a huge amount of benefit from being in the social mix of other kids the same age. He was in day-care from three months, part-time, and even at five months, if we were away for a week, when he’d get back, the other babies were over the moon – they recognised each other. I hadn’t realised how early on that socialisation happens.

So you weren’t concerned about day-care at all. Some women get tied up in knots about putting their kids in day-care. I know – there’s this thing about guilt. It is actually the best environment – they [pre-school educators] can do a much better job than me. If my time pressure is relieved by not having to have every moment dealing with all the stuff you have to deal with young kids … he’s come out as being a very sociable child and that he learnt from early on. Guaranteed when you’ve got the most important meeting, and your husband has a most important meeting at exactly the same time, that’ll be the time your kid gets sick. So you have to have a backup.

So what advice do you give other academic mums? Don’t stress – there are ways around. And the meeting you think is most important doesn’t have to be the most important. You just juggle everything you have as well as you can, and there are ways around any hurdle or hiccup. Just keep out there. It’s really important for other younger women to see women in senior roles.

Are universities doing the necessary to help women make the most of their talents in data science? I think it’s still a struggle. I think there’s been bureaucratic pushes for gender equality, which is really how I actually got an academic position in the first place in the US.

How so? Equal opportunity. Many statistics departments had no women, and it was a cultural shift in the early 1990s that many university administrations were forcing departments to hire women … or otherwise they couldn’t hire … if they [universities] were doing it well, they were not putting women in that situation of thinking, “Oh I was only hired because I was a woman”. They were doing it in the sense of making sure that women realised that they were talented, and wanted for their talents, not just because of the administration push. But that wasn’t universal.

I thought things have been solved, but it’s not. Time and time again women are evaluated differently at promotion, and in classroom evaluations, they are not on average [rated to be] as good as the men, and that’s been shown again and again and again. So the thing is, don’t get put off by that; you will sometimes need to fight for your promotions and have people willing to fight for you.

Systemically, things are still not weighted fairly between men and women. It’s not. I’ve just finished studying some of the research-grant rates in Australia and the number given to women faculty are pitiful, from both the Australian Research Council and the National Health and Medical Research Council, which is the health sciences. That impacts whether women can get through to those higher ranks. That’s my next fight.

Would you see yourself as a crusader? How do you define yourself in exposing these inequalities? We’ve seen a lot of things [around sex, privilege and power discussed] in public in these last few months, with the sex scandals in Hollywood. I’ve seen that all through my career in academia. I think we, hopefully, are on a cusp where the playing field for recognising talent among women becomes more level … I had advantages early on, and I feel like I need to pay that back.

I wouldn’t say I’m a crusader; I’m saying I see where we’ve come from, in terms of generations of women in my family, and where we are now, and we’ve come a long, long way. I’ve had so many more opportunities than my mum and my grandmother … I feel like I’ve got a responsibility to those generations to keep it moving in the right direction.

What advice would you give young women looking at a career in data science? What skills and attributes do they need to develop? Get onto the publicly available software – free software like R and Python – and get to know them. These are hugely powerful, and they give you power. There’s a number of courses you can do for free to help learn how to work with data.

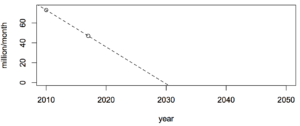

Any particular courses that you would recommend? There’s Data Camp and Corsera and Software Carpentry, among others. Work with data. Play. Extract somebody’s tweets and analyse the text – there are really good resources for that. Pull data from the government web pages – they have lots of information. The New Zealand Herald has lots of data available. Just get comfortable finding data, making plots of it, and seeing whether it matches up what the media is reporting about a problem. This is the sort of power you can get over your life if you can make decisions yourself, rather than being fed decisions.

Read more about Di Cook:

Her academic page

Wikipedia

Another Q & A

f Statistical Computing (Asian Regional Section) and the Operations Research Society of New Zealand at the University of Auckland, so we couldn’t miss the opportunity to talk with her. A brief bio: Di is a world leader in data visualisation and well-known for her work on interactive graphics. She is Professor of Business Analytics in the Department of Econometrics and Business Statistics at Monash University. She’s a Fellow of the American Statistical Association, elected member of the R Foundation and the Editor of the Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. Her research lies in data science, data visualisation, exploratory data analysis, data mining, high-dimensional methods and statistical computing.

f Statistical Computing (Asian Regional Section) and the Operations Research Society of New Zealand at the University of Auckland, so we couldn’t miss the opportunity to talk with her. A brief bio: Di is a world leader in data visualisation and well-known for her work on interactive graphics. She is Professor of Business Analytics in the Department of Econometrics and Business Statistics at Monash University. She’s a Fellow of the American Statistical Association, elected member of the R Foundation and the Editor of the Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. Her research lies in data science, data visualisation, exploratory data analysis, data mining, high-dimensional methods and statistical computing.