Simple and ineffective

Q: Did you see there’s a new test to predict dementia?

Q: Yes, the Herald says it “would allow drugs and lifestyle changes, such as a healthy diet and more exercise, to be more effective before the devastating condition takes hold.”

A: That would make more sense if there were drugs and lifestyle changes that actually worked to stop the disease process.

Q: At least it’s a simple one and accurate test. It’s just based on your sense of smell.

A: <dubious noises>

Q: But “almost all the participants, aged 57 to 85, who were unable to name a single scent had been diagnosed with dementia. And nearly 80 per cent of those who provided just one or two correct answers also had it, ”

A: That’ s not what the research says

Q: It’s what the story says.

A: Yes. Yes, it is.

Q: Ok, what does the research say? It’s behind a paywall

Q: That matches the story, doesn’t it?

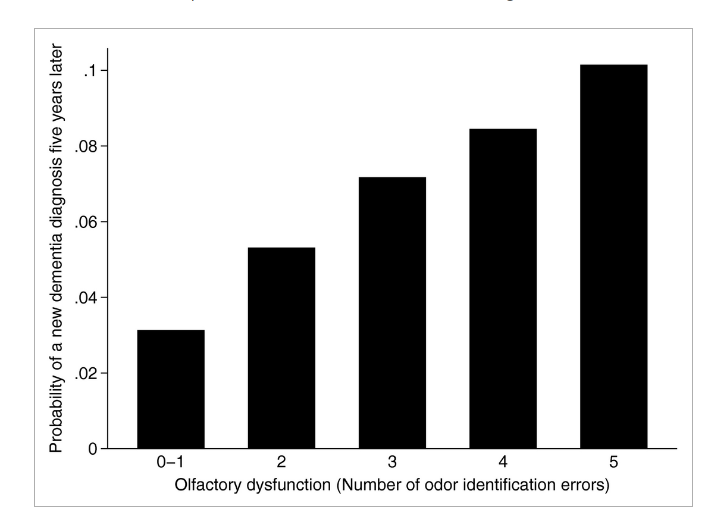

A: Check the axis labels.

Q: Oh. 8% and 10%? But couldn’t the labels just be wrong?

A: Rather than the Daily Mail? It’s possible, but the research paper also says “9% positive predictive value”, meaning that only 9% of those who are predicted to get dementia actually do, and that matches the graph.

Q: Um

A: And there’s a commentary in the same issue of the journal, headlined Screening Is Not Benign and saying “No test with such a low [positive predictive value] would be taken seriously as a way to identify any disease in a population”

Q: But it’s still a big difference, isn’t it.

A: Yes, and it’s scientifically interesting that the nerves or brain cells related to smell seem to be damaged relatively early in the disease, but it’s not a predictive test.

[Update: the source for the error seems to be the University of Chicago press release.]

[Update: It’s on Stuff, too]

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »