Effective treatment is effective

There’s a story in New Scientist, and in the NY Daily News, based on this research paper, saying that choosing alternative treatment instead of conventional treatment for cancer is bad for you.

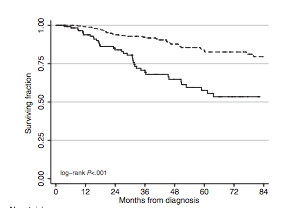

The research is well done: they looked at the most common cancers in the US and found a small set of people who turned down all conventional treatment in favour of ‘alternative’ medicine. They matched these people on cancer type, age, clinical group stage, what other disease they had, insurance type, race, and year of diagnosis, to a set who did get conventional treatment. Even after all that matching, there was a big difference in survival.

There are two caveats to the story. First, this is people who turned down all conventional treatment, even surgery. That’s rare. In the database they used, 99.98% of patients received some conventional treatment. It’s much more common for people to receive some or all of the recommended conventional treatment, plus other things — not ‘alternative’ but ‘complementary’ or ‘integrative’ medicine.

Second, the numbers are being misinterpreted. For example, New Scientist says

Among those with breast cancer, people taking alternative remedies were 5.68 times more likely to die within five years.

The actual figures were 42% and 13%, so about 3.1 times more likely. Here’s the graph

Similarly, the New Scientist story says

They found that people who took alternative medicine were two and half times more likely to die within five years of diagnosis.

The actual figures were 45% and 26%; 1.75 times more likely.

What’s happening is a confusion of rate ratios and actual risks of death; these aren’t the same. The rate (or hazard) is measured in % per year; the risk is measured in %. The risk is capped at 100%; the rate doesn’t have an upper limit. Because of the cap at 100%, risk ratios are mathematically less convenient to model than rate ratios. As a tradeoff, it’s harder to explain your results using rate ratios. The Yale publicity punted on the issue, not mentioning the numbers and leaving reporters to get it wrong. When this happens, it’s the scientists’ fault, not the reporters’.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »

It’s a shame New Scientist got it wrong as I have relied on them for news and trusted their stats eek!

8 years ago

The basic message is right, but the details are definitely wrong.

8 years ago