Big fat lies?

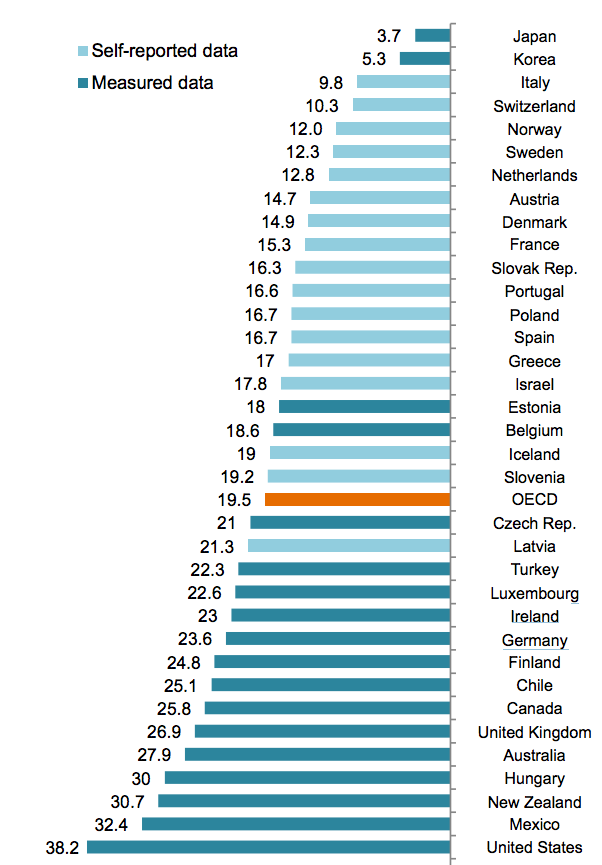

This is a graph from the OECD, of obesity prevalence:

The basic numbers aren’t novel. What’s interesting (as @cjsnowdon pointed out on Twitter) is the colour separation. The countries using self-reported height and weight data report lower rates of obesity than those using actual measurements. It wouldn’t be surprising that people’s self-reported weight, over the telephone, tends to be a bit lower than what you’d actually measure if they were standing in front of you; this is a familiar problem with survey data, and usually we have no real way to tell how big the bias is.

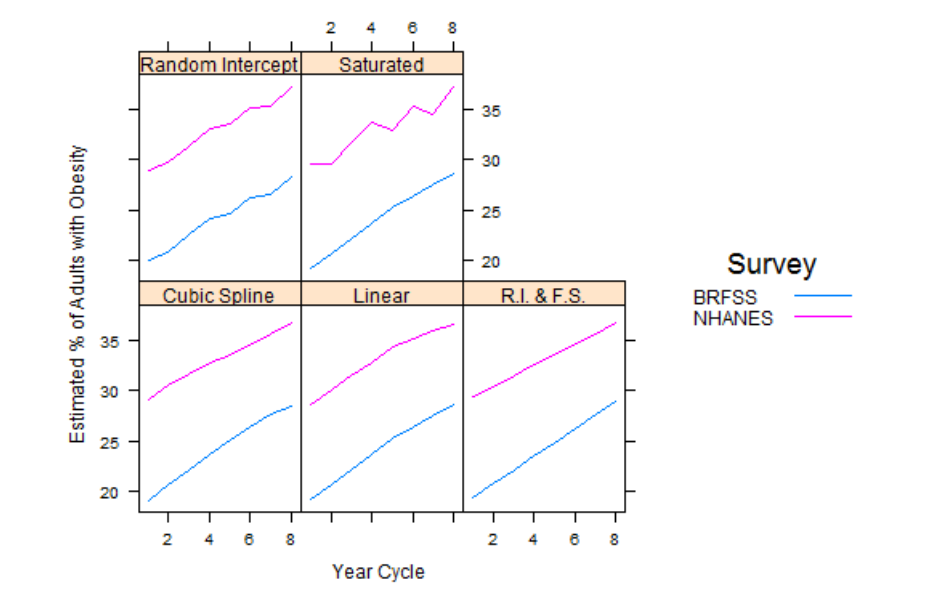

In this example there’s something we can do. The United States data come from the National Health And Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES), which involve physical and medical exams of about 5,000 people per year. The US also runs the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), which is a telephone interview of half a million people each year. BRFSS is designed to get reliable estimates for states or even individual counties, but we can still look at the aggregate data.

Doing the comparisons would take a bit of effort, except that one of my students, Daniel Choe, has already done it. He was looking at ways to combine the two surveys to get more accurate data than you’d get from either one separately. One of his graphs shows a comparison of the obesity rate over a 16-year period using five different statistical models. The top right one, labelled ‘Saturated’, is the raw data.

In the US in that year the prevalence of obesity based on self-reported height and weight was under 30%. The prevalence based on measured height and weight was about 36% — there’s a bias of about 8 percentage points. That’s nowhere near enough to explain the difference between, say, the US and France, but it is enough that it could distort the rankings noticeably.

As you’d expect, the bias isn’t constant: for example, other research has found the relationship between higher education and lower obesity to be weaker when using real measurements than when using telephone data. This sort of thing is one reason doctors and medical researchers are interested in cellphone apps and gadgets such as Fitbit — to get accurate answers even from the other end of a telephone or internet connection.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »