Believing surveys

There was a story on Stuff yesterday claiming that 85% of Kiwis brush their teeth too hard, based on a survey by a company that sells soft toothbrushes. The survey involved over 1000 people, and that’s about all we know, except that the reported rate of twice-per-day brushing was about 15 percentage points higher than in the 2009 NZ Oral Health Survey.

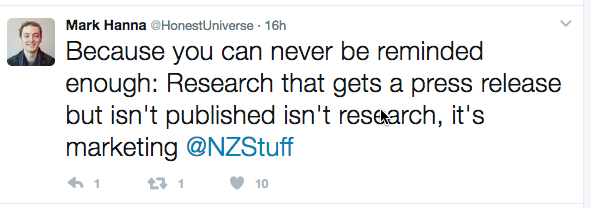

Mark Hanna tweeted about the press release by survey issue

I want to expand on this. Why is research, especially survey research, different? When David Fisher interviews people involved with gambling addiction, we don’t need anything more than his story. When Fletcher Building says they are cutting $150m from their profit estimates, we don’t need anything more than their press release. So why isn’t enough that this toothbrush company says they have a survey?

The issue is responsibility. If an investigative journalist reports statements from people, it’s the journalist’s reputation that makes those reports credible. If there are anonymous sources, again it’s the reputation of the journalist and the newspaper that makes us believe the sources really exist and are their claims are credible. When a company says it’s introducing a new product or is revising its income estimates, the company is the only authoritative source of information, and the claims are treated as mere claims by the company, not as facts.

With a survey press release, the journalist typically isn’t vouching for the correctness of the interpretation or the validity of the methodology; that’s not their expertise. And we can’t tell from the toothbrush story whether it was a real survey, or a well-calibrated online panel, or whether it was just a bogus clicky poll on a website somewhere. There’s no attribution, and there’s no responsibility. Even so, the claims don’t get treated as mere advertising; they get reported in basically the same way as all research findings.

If we’re going to treat a survey of this sort as showing anything, and if the journalist isn’t vouching for the information, the minimum standard is that we can find out what was done. The company doesn’t need to nerd up its press release with details, but they can put them on a website somewhere — how they found people, what the response rate was, something about who they sampled, what the actual questions were. Or, if their survey was done by a reputable market research firm, tell us that, and at least we know someone who understands the issues is standing behind the claims.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »