Anti-smacking law

Family First has published an analysis that they say shows the anti-smacking law has been ineffective and harmful. I think the arguments that it has worsened child abuse are completely unconvincing, but as far as I can tell there isn’t any good evidence that is has helped. Part of the problem is that the main data we have are reports of (suspected) abuse, and changes in the proportion of cases reported are likely to be larger than changes in the underlying problem.

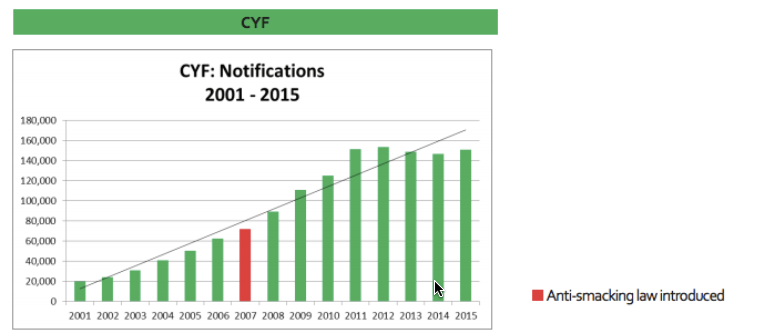

We can look at two graphs from the full report. The first is notifications to Child, Youth and Family

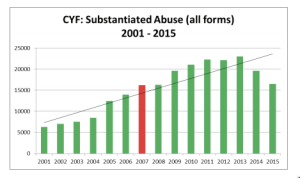

The second is ‘substantiated abuse’ based on these notifications

For the first graph, the report says “There is no evidence that this can be attributed simply to increased reporting or public awareness.” For the second, it says “Is this welcome decrease because of an improving trend, or has CYF reached ‘saturation point’ i.e. they simply can’t cope with the increased level of notifications and the amount of work these notifications entail?”

Notifications have increased almost eight-fold since 2001. I find it hard to believe that this is completely real: that child abuse was rare before the turn of the century and became common in such a straight-line trend. Surely such a rapid breakdown in society would be affected to some extent by the unemployment of the Global Financial Crisis? Surely it would leak across into better-measured types of violent crime? Is it no longer true that a lot of abusing parents were abused themselves?

Unfortunately, it works both ways. The report is quite right to say that we can’t trust the decrease in notifications; without supporting evidence it’s not possible to disentangle real changes in child abuse from changes in reporting.

Child homicide rates are also mentioned in the report. These have remained constant, apart from the sort of year to year variation you’d expect from numbers so small. To some extent that argues against a huge societal increase in child abuse, but it also shows the law hasn’t had an impact on the most severe cases.

Family First should be commended on the inclusion of long-range trend data in the report. Graphs like the ones I’ve copied here are the right way to present these data honestly, to allow discussion. It’s a pity that the infographics on the report site don’t follow the same pattern, but infographics tend to be like that.

The law could easily have had quite a worthwhile effect on the number and severity of cases child abuse, or not. Conceivably, it could even have made things worse. We can’t tell from this sort of data.

Even if the law hasn’t “worked” in that sense, some of the supporters would see no reason to change their minds — in a form of argument that should be familiar to Family First, they would say that some things are just wrong and the law should say so. On the other hand, people who supported the law because they expected a big reduction in child abuse might want to think about how we could find out whether this reduction has occurred, and what to do if it hasn’t.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »

Thanks for posting this thoughtful response Thomas, I saw it doing the rounds yesterday and had meant to forward it to you.

9 years ago

It would be interesting to look at the number of notifications per child (perhaps per quarter).

If the number of notifications per child is going up then it suggests more reporting is going on – especially if they are made by different people.

If more reports per child per “person reporting” is going up, it suggests that CYFs aren’t doing their job that well at substantiating abuse.

~~~

Of course, we don’t know what may have happened in the future that never was. Perhaps parents, emboldened by the being allowed the right to smack, used corporal punishment in more extreme ways … and fewer people felt it was their place to complain. Reporting rates go down but substantiated abuse rates go up.

~~~

Accident rates of children might also be worth looking at e.g. hospital discharge data. If rates of abuse are going up than accidents rates should be going up (assuming other injury types are staying constant). And also comparing between age groups – if 2-4 years old have injury rates increasing at twice the age of 12-14 year olds than something is going on.

9 years ago

Looking at hospital discharge data is a good idea — the report did, but only for mental health.

9 years ago

We had one of the people from MSD who is in charge of organising this data at a methodology meeting in 2014. While I can’t remember all the details I do remember there was some changes in the measurements and he was rather keen on some assistance in developing standard reporting.

Firstly, it is an administrative dataset, so if you change the administrative system, in this case giving people a stronger legal obligation to report, this can make comparisons problematic.

Secondly, they ended up with a lot more reports because they made reporting psychological abuse just as required as physical abuse. You can sort of see this as the substantiated to reporting ratio looks to be going down.

Like the old joke

“How are you today?”

“Compared to what?”

we need to check that we comparing numbers that are consistently measured.

9 years ago