Sometimes things are more complicated than they seem.

From the Herald

It might seem like a virtuous choice – but munching lettuce is worse for the planet than eating bacon, a study claims.

Researchers say the amount of energy and water used – and the level of greenhouse gases produced – is far greater per calorie for lettuce than pork.

The second sentence doesn’t look as if it can carry the weight of the first sentence. I mean, yes, maybe per calorie, but who gets most of their calories from lettuce? Not even rabbits.

Later on, the story points this out:

Richard Bennett, dean of food research at Reading University, said: “The calorie is not the most sensible functional unit of comparison.”

and ends

But the study conceded that eating fewer calories would lead to better public health, benefiting the environment and cutting energy use.

That seems to settle it: Study 0, lettuce 1. Until you go and look at the research.

The research isn’t actually about working out the relative impacts of bacon and lettuce, it’s about a much less trivial question. It would probably be a good thing for the US population, on average, to lose weight. It would probably also be a good thing for the US population to eat more fruit and vegetables. What does that imply about food production and resource use?

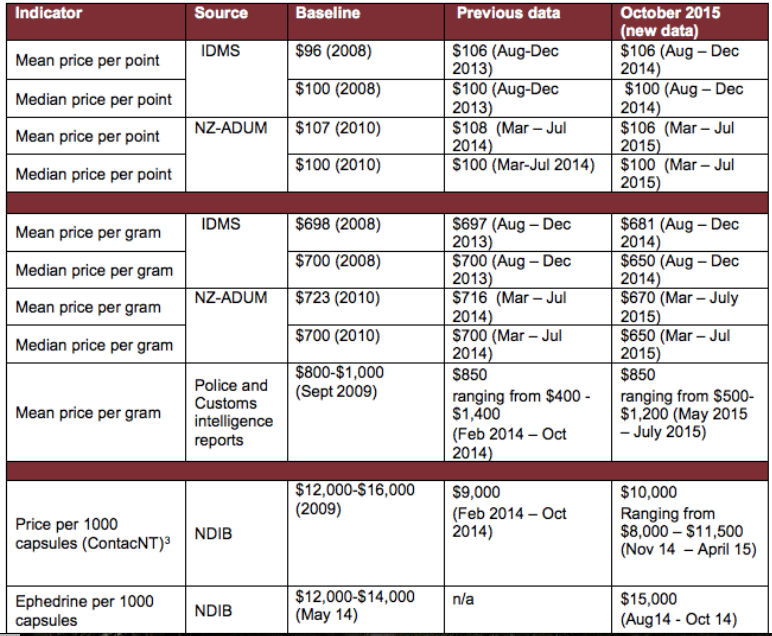

In the research, they considered three scenarios: keep eating unhealthy stuff, just less of it to reduce obesity; eat healthier food without reducing calorie intake; and eat healthier food at a lower total calorie intake to reduce obesity. The per-calorie resource demands for various foods are an input to this calculation; they aren’t conclusions in themselves.

The second scenario is the worst environmentally, but that’s not really surprising. What’s interesting, and basically missed in the reporting is that the third scenario is worse than the first. If people in the US changed their diets to eat less and to follow dietary recommendations, the result would be an increase in greenhouse-gas emissions, in water use, and in energy use. Reducing meat consumption, especially beef, would help the environment, but reducing use of cheap fats, sugars, and starches wouldn’t, and increasing consumption of the current mix of fruit and vegetables definitely wouldn’t

To some extent, the conclusions are US-specific. NZ fruit and vegetable production uses less irrigation, and the produce is shipped shorter distances, in milder climates, than in the US. The conclusions also assume business as usual in food production. With cheap petrol and cheap water, it made sense to grow everything in the Imperial Valley and truck it or fly it across the country; in the future, that may not be efficient and the mix of fruits and vegetables consumed may change.

Carbon pricing and water shortages are going to increase the cost of food. The interesting part of this analysis is that they will increase the cost of healthier diets (at least in the US) even more, at least until the industry works out ways to adapt.