The death of the novel?

So, the Guardian has a list of the top-100 best ever novels written in English. There’s the usual problem that lit people have with genre (can it really be true that The Moonstone is the best detective novel in English?), but I’m not an expert in novels.

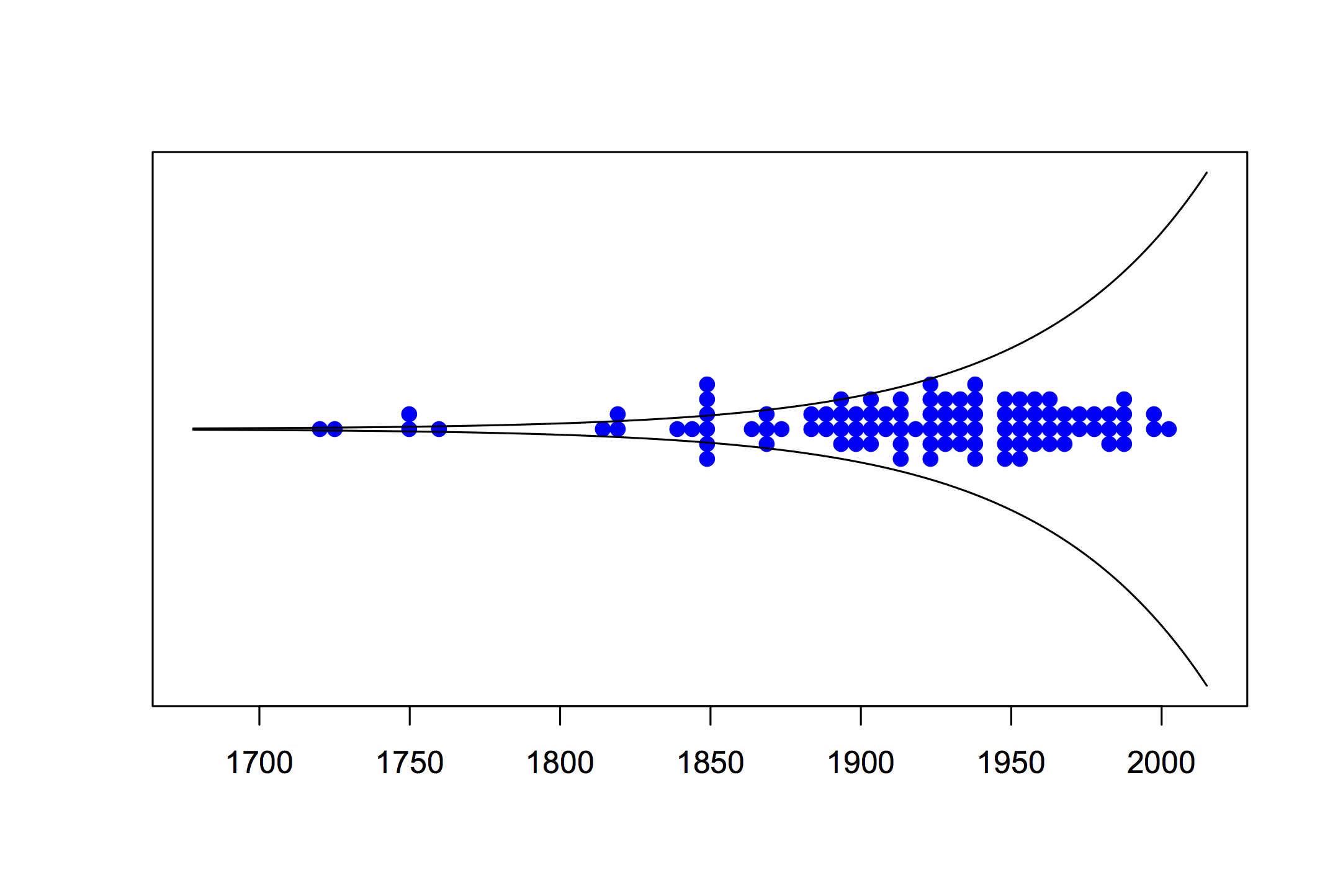

There have been complaints about the diversity of the list, and that’s where there’s a definite statistical anomaly. The books are old. For example, 33 of them come from before the start of the twentieth century and none of them from after the end of the twentieth century, even though many more novels were published in the latter period.

An article in Seed magazine, and its technical notes tried to estimate the number of new book authors each year over time. That’s not quite the same thing, since we aren’t considering only first books and are considering only novels. However, it’s a reasonable surrogate. Using their estimates, as many books were published before 1930 (55 places on the list) as after 2000 (no places on the list). Here’s a graph, with the dots indicating books on the list and the lines indicating total published.

As I said, this isn’t my field. Maybe nineteenth century novels really were hundreds of times more likely to be ‘great’ than modern novels. But it’s not the only possible explanation.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »

I think that nineteenth century novels are more likely than modern novels to be considered “great” ex definitione. “Greatness” is not that much description of quality of work as it is description of importance, historical significance of work. Any novel that accurately described some phenomenon/historical event, provoked social or political change, inspired other “great” works or authors or paved the way to something substantial is likely to be considered “great”. Obviously we can’t accurately predict historical importance of contemporary works, so we can assign “great” label only in retrospect.

It’s the same thing as Nobel prize, which is often granted for research done quite a few years ago. Especially in case of basic research, it’s importance is proven only by further work build on top, and further work needs time to appear.

10 years ago

Possibly, up to a point. Even if we stipulate that, it would be surprising that there are so few post-WW2 novels. Thirty or forty years should be plenty of time.

10 years ago

I would suggest that books published after 2000 have trouble being “great” without withstanding the test of time. I do not know how “great” is defined in this ranking, but it must be harder to eliminate biasing factors like media fads, current fashions, connections with current events and so on when judging a contemporary novel. Which is why winners of major literary prizes like the Booker or the Goncourt often vanish into oblivion after a few dozen years. This is also true for the Nobel.

10 years ago

I wonder how much of this is the inability to really judge a novel when you are still in the same cultural context?

Similarly, I also note the cost of publishing has dropped over time. Perhaps expense was a strong filter on quality? It doesn’t have to be, and might even be the reverse in some contexts, but it also could be a reason.

That said, it’s also a pretty good hypothesis that alternative media (TV, Movies) have engaged writers who might have been novelists or short story authors in a bygone era.

But it isn’t my field either, so I have no idea how to test between these hypotheses (or even if all of them might be true in some degree, or if I have missed the main driver completely).

10 years ago