Who is my neighbour?

The Herald has a story with data from the General Social Survey. Respondents were asked if they would feel comfortable with a neighbour who was from a religious minority, LGBT, from an ethnic or racial minority, with mental illness, or a new migrant. The point of the story was that the figure was about 50% for mental illness, compared to about 75% for the other groups. It’s a good story; you can go read it.

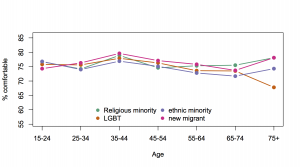

What I want to do here is look at how the 75% varies across the population, using the detailed tables that StatsNZ provides. Trends across time would have been most interesting, but this question is new, so we can’t get them. As a surrogate for time trends, I first looked at age groups, with these results [as usual, click to embiggen]

There’s remarkably little variation by age: just a slight downturn for LGBT acceptance in the oldest group. I had expected an initial increase then a decrease: a combination of a real age effect due to teenagers growing up, then a cohort effect where people born a long time ago have old-fashioned views. I’d also expected more difference between the four questions over age group.

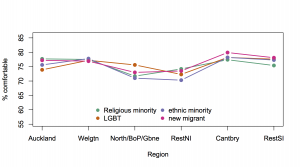

After that, I wasn’t sure what to expect looking at the data by region. Again, there’s relatively little variation.

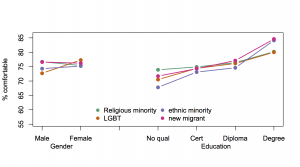

For gender and education at least the expected relationships held: women and men were fairly similar except that men were less comfortable with LGBT neighbours, and comfort went up with education.

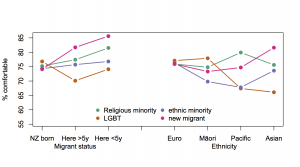

Dividing people up by ethnicity and migrant status was a mixture of expected and surprising. It’s not a surprise that migrants are happier with migrants as neighbours, or, since they are more likely to be members of religious minorities, that they are more comfortable with them. I was expecting migrants and people of Pacific or Asian ethnicity to be less comfortable with LGBT neighbours, and they were. I wasn’t expecting Pacific people to be the least comfortable with neighbours from an ethnic or racial minority.

As always with this sort of data it’s important to remember these responses aren’t really level of comfort with different types of neighbours. They aren’t even really what people think their level of comfort would be with different types of neighbours, just whether they say they would be comfortable. The similarity across the four questions makes me suspect there’s a lot of social conformity bias creeping in.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »

“social conformity bias”

Are there good techniques for overcoming this?

10 years ago

Overcoming it in oneself, I don’t know. Especially without going the other way and becoming a reflexive contrarian. The people at LessWrong talk about this, but I don’t know if they have anything useful.

Overcoming it in groups: the Asch conformity experiments suggest that even a small amount of non-conforming opinion makes it easier for other people not to conform.

10 years ago

In collaboration with scientists, one useful thing for statisticians to be able to do is ask for reasons why people believe things. “I don’t understand this, I’m just a statistician, can you tell me how you worked out this grass was grue rather than green?”

10 years ago

Thanks! Interesting stuff.

However I realise my original question was unclear. I was trying to ask whether there were survey techniques for trying to overcome potentially dishonest responses and get a more accurate picture of people’s ‘true’ thoughts and feelings. I’m aware of the old randomised reponse thing. Do people use that (or more sophisticated things) in practice?

10 years ago

Randomised response doesn’t work as well as it was supposed to — for it to work, the respondent needs to understand the point and trust the way it’s implemented. It’s really most useful in situations where the concern is the researchers being coerced to reveal information about, say, criminal acts.

What seems to work for things people are just unwilling to say is computer-based interviewing.

10 years ago