Misunderstanding genetic heritability

From the Herald, under the headline “Is this why we’re all getting fat?”

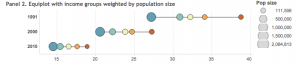

According to the UN’s World Health Organisation, obesity nearly doubled worldwide from 1980 to 2008.

More than 2.8 million adults die each year as a result of being overweight or obese, it says. A full 42 million children under the age of five are considered to be obese.

Diet and a sedentary lifestyle have long been fingered as causes of obesity, but in recent years, advances in gene sequencing have turned attention to inheritance.

Previous studies have variously estimated genes as being to blame for between 40 and 70 per cent of the problem.

Every sentence here is true, but the impression is completely wrong.

The 40-70% genetic contribution to weight is comparing different individuals in basically the same environment. The ‘obesity epidemic’ is comparing whole populations over time. One thing we know can’t possibly explain the recent increases in obesity is genetics: there hasn’t been time for the genes of these populations to change.