Women are from Facebook?

A headline on Stuff: “Facebook and Twitter can actually decrease stress — if you’re a woman”

The story is based on analysis of a survey by Pew Research (summary, full report). The researchers said they were surprised by the finding, so you’d want the evidence in favour of it to be stronger than usual. Also, the claim is basically for a difference between men and women, so you’d want to see summaries of the evidence for a difference between men and women.

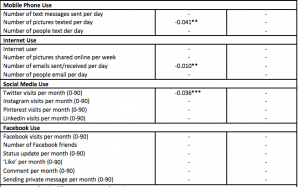

Here’s what we get, from the appendix to the full report. The left-hand column is for women, the right-hand column for men. The numbers compare mean stress score in people with different amounts of social media use.

The first thing you notice is all the little dashes. That means the estimated difference was less than twice the estimated standard error, so they decided to pretend it was zero.

All the social media measurements have little dashes for men: there wasn’t strong evidence the correlation was non-zero. That’s not we want, though. If we want to conclude that women are different from men we want to know whether the difference between the estimates for men and women is large compared its uncertainty. As far as we can tell from these results, the correlations could easily be in the same direction in men and women, and could even be just as strong in men as in women.

This isn’t just a philosophical issue: if you look for differences between two groups by looking separately for a correlation each group rather than actually looking for differences, you’re more likely to find differences when none really exist. Unfortunately, it’s a common error — Ben Goldacre writes about it here.

There’s something much less subtle wrong with the headline, though. Look at the section of the table for Facebook. Do you see the negative numbers there, indicating lower stress for women who use Facebook more? Me either.

[Update: in the comments there is a reply from the Pew Research authors, which I got in email.]

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »

This is an email from the Pew Research authors, posted with their approval

Dear Dr. Lumley:

We noted your post on our research and a news piece covering it and wanted to make sure we understand the issues you raise about our work – and also explain more about it.

The issue you raise is that we were comparing men and women but that we didn’t directly compare whether men and women vary significantly from each other. If we understand your comments correctly, you suggest that a better comparison would have been achieved through a partially constrained model that pooled men and women into a single regression, rather than the separate unconstrained model that we adopted. Your suggestion has merit, and this was something we explored during our early analysis. After careful consideration, we adopted a different approach.

Our observation that men and women experience stress differently and that they often self-select into different uses of technology is not new. These already-established facts guided our methodological choices. Indeed, we began our report with a simple comparison of mean perceived stress: “In this survey, women report an average score of 10.5 out of 30 on the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). Men reported an average score of 9.8 — a figure that is 7% lower than women.” We verified and report this with an ANOVA (p. 11 of our report). This conclusion is not disputed in the literature on psychological stress. Similarly, our prior work has verified that women and men use different technologies at different rates.

For these reasons, and “because men and women tend to experience stress differently, we ran each of our analyses separately for men and for women” (p. 4 of our report).

We began our analysis with an exploratory approach to test what technologies and what life events predict stress separately for women and men. We believe that the alternative approach, one using a partially constrained model with interaction effects to test if the variance is different between men and women, assumes more shared variance than actually exists. Such a model would increase multicoliniarity and inflate the standard errors. As you point out, this would reduce the likelihood that we would find statistically significant differences between men and women. However, because of the assumptions behind this approach, it may not be a better representation of the truth behind our data.

Every analysis consists of dozens of small and not-so-small choices that are made in an attempt to present the most truthful story in the data. There is no agreed-upon standard for adopting unconstrained vs. constrained models — and clear preferences in different scholarly disciplines where we may diverge. Any time two procedures are used to test the same hypotheses, you can end up with different p values. In this case, we felt had a strong theoretical reason to think that men and women experience stress and use technology differently. This gave us a clear rationale for the choices we made in presenting our data.

We demonstrated that some technologies and some life events predict stress in women, but not men. We felt we were clear and careful in how we interpret this in the report.

10 years ago