Petitions and polls

Today is the 120th anniversary of women’s suffrage in New Zealand, with commemorations in a range of places, including the Centenary fountain in Khartoum Place, Auckland

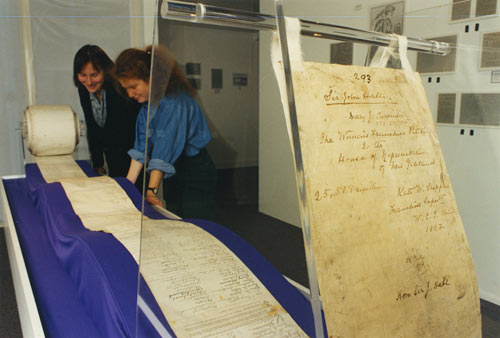

The petition for women’s suffrage, signed by about 24000 women, was submitted to Parliament in July 1893

and the names of the petitioners have been digitised and made available at New Zealand History Online.

I haven’t been able to work out exactly what the adult female population of NZ was at the time, but the digital yearbook says that there were 305287 non-Maori females, that 30.94% were married and 4.11% widowed, and that there were 67000 never-married females 15 and older. Depending on how many of the never-married 15+ were 21 or older, this gives perhaps 150000, so about 16% of the non-Maori adult female population signed the petition. That compares to modern petitions with about 2.4% of voting-age people opposing marriage equality and about 10% for the anti-asset-sales petition (though these are targeting the entire NZ voting population, not just women).

Presumably, rather more than 16% of women were in favour of getting the right to vote, but it’s always difficult to track people down and get them all to sign. In 1893 there wasn’t an alternative: sampling hadn’t been invented, and would likely have been impractical — certainly, calling random phone numbers wouldn’t have got you very far.

Today, we have much more accurate ways of estimating the proportion of people who support some government action. Petitions, like demonstrations, are mostly useful for signalling to the government that some issue they weren’t aware of is actually important. For example, the petition against animal testing for legal highs would have been effective to the extent that the government wasn’t aware people cared about the issue. For anyone who was aware this was a political issue, a well-conducted opinion poll would be more informative and should be both less expensive and more effective than a petition.

Referendum petitions, as in New Zealand and some parts of the US, are an example of this principle: if an issue can get the support of 10% of the NZ voting population, it’s probably important enough to be worth serious consideration and debate. The threshold is weaker in many places. For example, in California a petition need only get 5% of the number of people who voted in the last election for state governor, which currently comes to under 2% of the adult population.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »

My great grandmother appears to have signed twice.

12 years ago

I think you’ve made a statistical error.

You state that “about 16% of the non-Maori adult female population signed the petition”.

However, a lot of the signatories would have been Maori women (Maori made up a much larger percentage of the population back then than they do today).

Therefore, the percentage of non-Maori adult females who signed the petition was lower than 16%.

12 years ago

Not a statistical error, perhaps a historical one.

I knew that Meri Te Tai Mangakahia was on the mural at the fountain because she requested the vote for women from the Kotahitanga. Her name isn’t on the petition, and a little browsing didn’t show any obviously Maori names, so I thought this indicated a separate process.

12 years ago