The Herald, overcoming its dislike of education league tables, says that NZ degrees are the most worthless in the developed world

New Zealand is at the bottom of the global league tables. The net value of a man’s tertiary education is just $63,000 over his working life, compared with $395,000 in the US. For a Kiwi woman, it’s $38,000 over her working life.

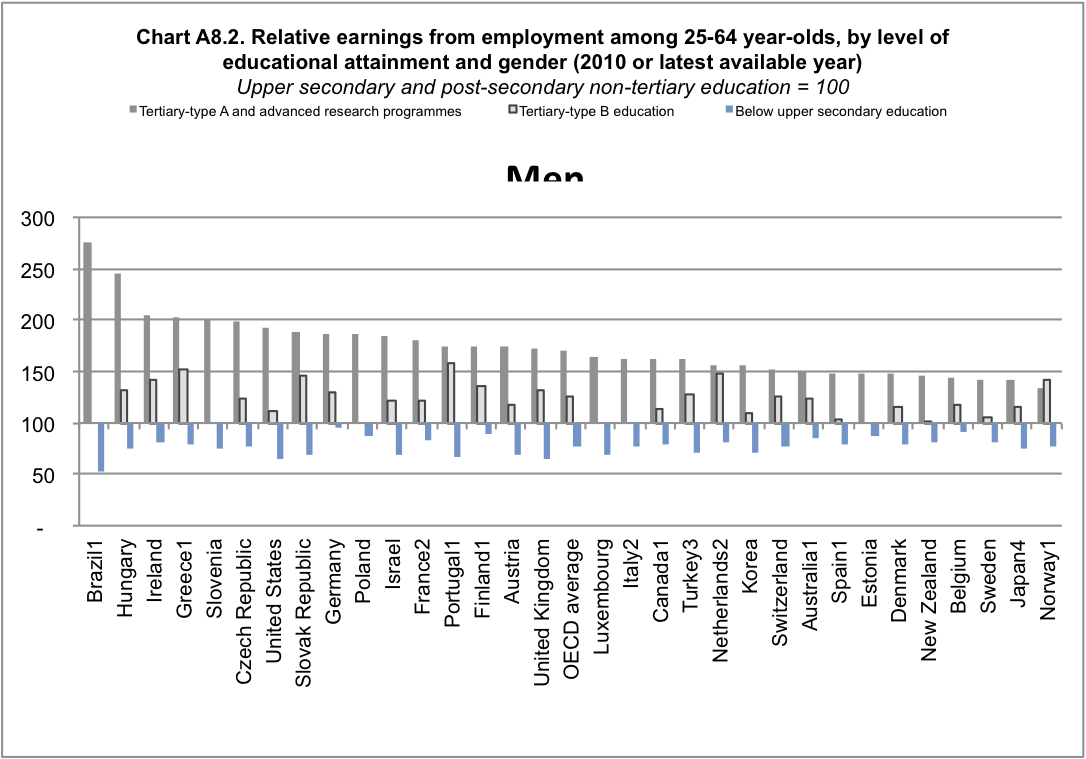

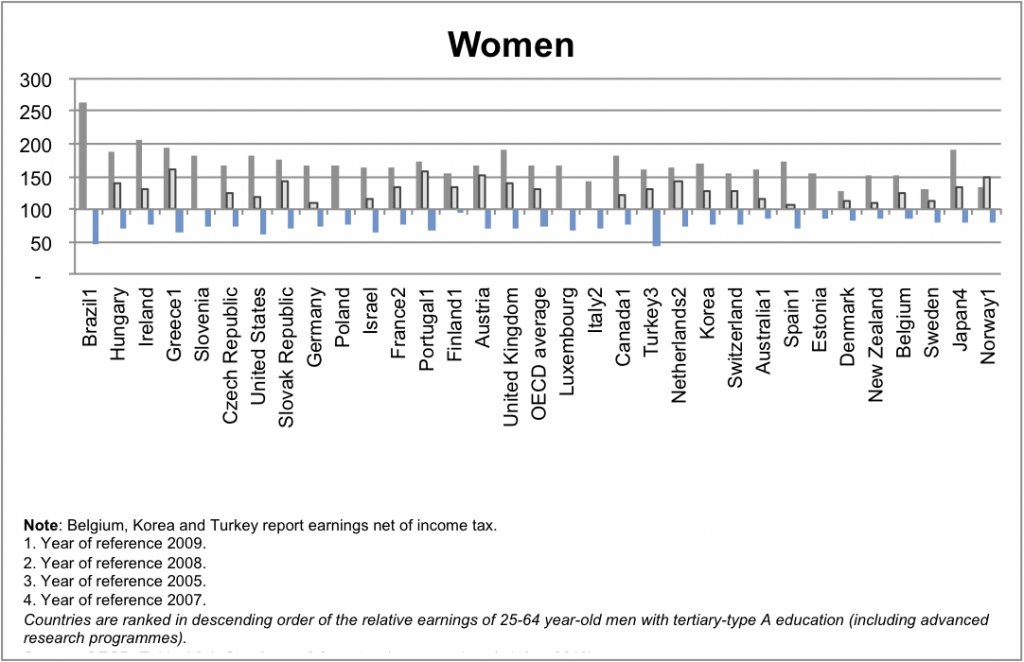

They don’t actually say what OECD report they looked at, but if you go to the OECD Directorate for Education and look at the most recent report, you can get these graphs (click to embiggen)

From the graphs, it’s fairly clear that for ‘Tertiary type-A and advanced research” degrees, NZ is not in fact at the bottom, but people with “Tertiary B-type” degrees do not seem to have any difference in income from those without degrees. So what are these types: Type A is

Largely theory-based programmes designed to provide sufficient qualifications for entry to advanced research programmes and professions with high skill requirements, such as medicine, dentistry or architecture. Duration at least three years full-time, though usually four or more years

and Type B is

Programmes are typically shorter than those of tertiary-type A and focus on practical, technical or occupational skills for direct entry into the labour market, although some theoretical foundations may be covered in the respective programmes. They have a minimum duration of two years full-time equivalent at the tertiary level.

So, people with traditional university degrees do earn more in NZ, but people with other tertiary qualifications may well not. It’s also important to remember that these are people in NZ with these degrees: the earnings of Kiwis who migrate overseas are not counted, but the degrees of migrants to NZ are counted even if they aren’t really recognised here.

The other interesting thing about the graph is who else is at the low end: Norway is at the bottom, Sweden and Denmark are both low. It’s useful to think about the reasons that people with university degree might have higher incomes

- Specific training: your degree gives you skills and knowledge that are helpful in your specific occupation

- General training: a degree gives you transferable skills that are helpful in many occupations

- Signalling: completing a degree shows employers that you can complete a degree

- Stratification: higher education is a way for the wealthy to perpetuate their advantages through hiring ‘people like us’ for good jobs

The first two of these are beneficial to the individual and to society as a whole. The third may be beneficial to the individual, but not to society as a whole, and the fourth is actively harmful. Among developed countries, those with low social mobility (such as the UK and the USA) have larger differences in income between those with and without degrees than those with higher social mobility (such as the Scandinavian countries).

This context sheds a different light on one of the comments quoted by the Herald

Employers and Manufacturers Association boss Kim Campbell agreed. People at the top in business weren’t paid anything near what counterparts overseas were getting because we didn’t have the big companies that paid top dollar.

A top-level executive in New Zealand would be lucky to get 10 times the entry-level pay rate, he said. In the US, it was not uncommon to get 200 times that level.

You don’t have to be a raving lefty to be dubious about this as an argument in favour of the US system.