Cancer survival up, deaths constant?

The Age (yes, I’m just back from the West Island) has an article on the annual cancer statistics report from the Victorian Cancer Council. Survival from diagnosis is up for many cancers, and that’s the headline, but in only some of these diseases is there a reduction in the death rate.

The problem is that survival from diagnosis measures the interval between two time points: diagnosis, and death. You can increase your survival time by dying later, which is a Good Thing, or by being diagnosed earlier and dying at the same time, which many people would consider bad.

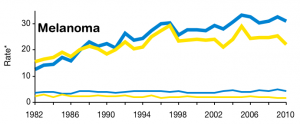

As an example, consider the graph of melanoma incidence and mortality in Victoria from the report.

The thicker lines are age-adjusted diagnosis rates per 100,000 people, the thinner lines are age-adjusted deaths per 100,000 people. Blue is for men, yellow is for women.

There has been a steady increase in melanoma diagnoses, especially for men, with a slight suggestion that a downturn may be beginning. The mortality rates are pretty much constant over twenty years. Survival from diagnosis, however, has been steadily improving for half a century.

From these data we can’t tell to what extent

- melanoma is increasingly common, but early detection and treatment has stopped this translating to an increase in deaths, versus

- melanoma happens just as it always did, and modern medicine does nothing more than diagnose it earlier.

For some cancers we do know what is happening. In childhood cancers there isn’t room for much lead-time bias, and treatment for many of them has been extremely successful. We know from randomized trials that mammography leads to fewer breast cancer deaths as well as earlier diagnoses, so that the increase in survival in breast cancer is a mixture of dying later and being diagnosed earlier. Similarly, we know that spiral CT scans in smokers reduce lung cancer mortality, though only by about 20%.

In other cancers it really isn’t clear. For example, there’s a lot of controversy over the benefit or harm of screening for prostate cancer, and a draft report from the US Preventive Services Taskforce is now recommending against.

For melanoma there hasn’t been much evaluation of screening. This may be partly because the hope was that screening would be extremely effective and the benefits would show up in the mortality statistics without needing any experimental studies. The reality has been disappointing. Screening for melanoma certainly increases survival time from diagnosis, and it’s unlikely to do much harm, but there’s remarkably little evidence that it’s expanding the useful end of the diagnosis-death interval.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »