Meddling kids confirm mānuka honey isn’t panacea

The Sunday Star-Times has a story about a small, short-term, unpublished randomised trial of mānuka honey for preventing minor illness. There are two reasons this is potentially worth writing about: it was done by primary school kids, and it appears to be the largest controlled trial in humans for prevention of illness.

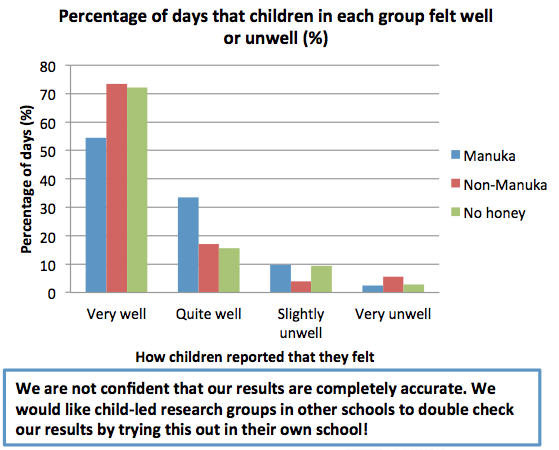

Here are the results (which I found from the Twitter account of the school’s lab, run by Carole Kenrick, who is named in the story)

The kids didn’t find any benefit of mānuka honey over either ordinary honey or no honey. Realistically, that just means they managed to design and carry out the study well enough to avoid major biases. The reason there aren’t any controlled prevention trials in humans is that there’s no plausible mechanism for mānuka honey to help with anything except wound healing. To its credit, the SST story quotes a mānuka producer saying exactly this:

But Bray advises consumers to “follow the science”.

“The only science that’s viable for mānuka honey is for topical applications – yet it’s all sold and promoted for ingestion.”

You might, at a stretch, say mānuka honey could affect bacteria in the gut, but that’s actually been tested, and any effects are pretty small. Even in wound healing, it’s quite likely that any benefit is due to the honey content rather than the magic of mānuka — and the trials don’t typically have a normal-honey control.

As a primary-school science project, this is very well done. The most obvious procedural weakness is that mānuka honey’s distinctive flavour might well break their attempts to blind the treatment groups. It’s also a bit small, but we need to look more closely to see how that matters.

When you don’t find a difference between groups, it’s crucial to have some idea of what effect sizes have been ruled out. We don’t have the data, but measuring off the graphs and multiplying by 10 weeks and 10 kids per group, the number of person-days of unwellness looks to be in the high 80s. If the reported unwellness is similar for different kids, so that the 700 days for each treatment behave like 700 independent observations, a 95% confidence interval would be 0±2%. At the other extreme, if 0ne kid had 70 days unwell, a second kid had 19, and the other eight had none, the confidence interval would be 0±4.5%.

In other words, the study data are still consistent with manūka honey preventing about one day a month of feeling “slightly or very unwell”, in a population of Islington primary-school science nerds. At three 5g servings per day that would be about 500g honey for each extra day of slightly improved health, at a cost of $70-$100, so the study basically rules out manūka honey being cost-effective for preventing minor unwellness in this population. The study is too small to look at benefits or risks for moderate to serious illness, which remain as plausible as they were before. That is, not very.

Fortunately for the mānuka honey export industry, their primary market isn’t people who care about empirical evidence.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »

The illnesses under study are contagious so treating kids as independent observations is a little dubious.

It would be interesting to compare when kids felt unwell and what their friendship/contact networks are.

Maybe a cross-over study would be better study design (watching out for seasonality effects).

10 years ago

I did also give the confidence interval for days within kid being as far from independence as possible.

I’m not sure that contagion matters. As you say, it depends on the social network structure, but to the extent that these kids tend to share a social network the randomisation is within this network, so a lot of it will cancel out.

10 years ago

I’d be a little worried about the issue because the social networks of boys and girls tend to be different. And there are differences in the way they interact in their social groups. Perhaps there was a “Typhoid Mary” that infected one group disproportionately. That’s why the timing of infections would be interesting.

The other thing I heard a few weeks ago on NatRad was that IIRC there is not a standard for manuka honey. Anyone can slap a label on honey and call it manuka honey … and they do so because they get a good price for it.

10 years ago